This article is featured in the Fall 2023 issue of Texas LAND magazine. Click here to find out more.

I was born and belong to the island of Newfoundland, part of Canada’s most easterly province. It is a place of staggering beauty and unrelenting presence. It possesses a raw physicality that invades every breath and every secret place of the heart. Newfoundland is a place not so much where people live, but rather, is a place those born to it cannot live without.

Larger than Ireland, the “rock,” constantly reminds its citizens of the North Atlantic’s enveloping presence, its gales and explosive seas, its dense fogs and creeping mists; and, in season, its dazzling jewels of sea-borne ice. Like the land itself, Newfoundlanders have been shaped by these elemental forces and by our pursuit of the wild abundance that surrounded us.

My early boyhood world was one of small and isolated communities, of unlimited freedom and continuous encounter with a natural world that provided everything, a place of joy and play, of learning, and sometimes of danger and fear. There was, simply, your house and the outdoors. No transitional space existed.

It was a world of cooperation and familiar self-reliance and intimate engagement with nature. It gave Newfoundlanders an unshakeable belief in themselves and a humility amidst the incontrovertible dependence we shared with all other life forms. This island made me the boy I was and the man I have become.

At the heart of things, nature was our language. None of the people I grew up with considered themselves ecologists, of course, but I have come to understand that this is exactly what and who they were. . . men and women learned in the systems and dynamics of nature. They were also the most capable and self-reliant people I have ever known. And they remain the kindest. From shipwrecks to the United States’ 9/11 disaster, the generosity of Newfoundlanders has rightfully become something of legend.

Thus, for the boy whose first memories are, not of family, but of catching bees amongst stinger nettles and luring snowbirds with breadcrumbs spread on the sea ice in the frigid grey of the northern Newfoundland winter, it was never a question as to what I would do when I grew up. I would, in fact, never grow up. I would pursue my boyhood love of animals and nature as a profession and, like a professional athlete, I would just continue playing for as long as I could, and in the place that I loved.

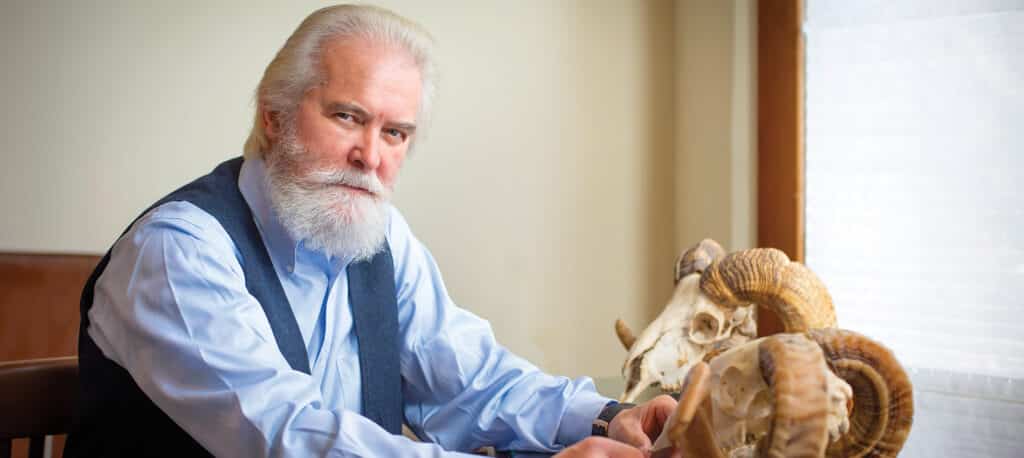

So, I studied to become a biologist, racing through a seven-year program of Bachelor of Science Honours and Master of Science degrees in slightly less than five years and very soon after joined the Provincial Government Wildlife Agency. I quickly moved on to lead provincial wildlife research and various other science programs. Ultimately, I founded a biodiversity institute supporting graduate student research in numerous countries.

Over a 30-year period, I experienced an unending pageant of extraordinary natural engagements, while never losing sight of the lifestyle and values of my Newfoundland culture. Such remembrances centered my conservation perspective, perceiving human and non-human life as equal and inseparable, and bonded by a shared interdependence within nature. For me, placing humans outside the natural cycle, and recommending a non-utilitarian, voyeuristic role for the human animal makes absolutely no sense. That cannot lead to a natural life for it is, in fact, entirely unnatural. Thus, I agree land must be preserved and protected; but I also believe landscapes should be viewed as livable and sustaining ecosystems for all species, and that the human animal should also forage there, sustainably, equitably, like all species, to the fullest extent possible.

Conservation Visions

These are the core values I brought to Conservation Visions, the organization I formally launched in 2015 and now lead. Located in the place I love, its channels of work and influence extend to many important conservation institutions worldwide, such as the World Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD). Supportive of diverse land and wildlife conservation approaches and deeply concerned for the welfare of animals, my organization’s work is centered on supporting legal and sustainable use of living natural resources as an ethical lifestyle and conservation incentive and actively managing lands to aesthetic and ecological abundance.

Conservation Visions is heavily engaged in what is known as the One Health approach to conservation. One Health encompasses a circular embrace, where healthy ecosystems, healthy wildlife populations and healthy human communities are seen as desirable, achievable—and inseparable. This focus mirrors my own life experiences with rural people who so clearly understood their responsibilities to the natural systems they themselves relied upon.

In advancing this perspective, Conservation Visions seeks to establish a view of all lands, public and private, first and foremost, as food provisioning systems for humans and all other species, and to instill an ethos in the owners of private lands and public land managers for conserving what is right and best on those landscapes. This includes working to return degraded lands to vitality, and to, in turn, become the best land stewards possible. It is a dream without margins, one for all people, everywhere.

I agree land must be preserved and protected; but I also believe landscapes should be viewed as livable and sustaining ecosystems for all species. . .

—Shane P. Mahoney

Wild Harvest Initiative®

To help achieve this vision I have founded the Wild Harvest Initiative®, a diverse, expanding and inclusive partnership of NGOs, state government agencies, outdoor industry proponents, federal agencies and private philanthropists in Canada, the United States and Europe, designed to quantify and provide value estimates for the wild meat, fish and other natural foods that are gathered by hunters, fishers and foragers in both countries. By focusing on the connections between wild food production and well-managed lands, I work to illustrate how those human-landscape relationships can return humanity to our original ecological role while reminding us all of the ongoing importance of wild food gathering for billions of people worldwide.

The Wild Harvest Initiative now holds the largest collection of data on recreational wild meat and fish harvests in the world. It is far more than a cute title or collection of recipes. The knowledge base and empirical value assessments it provides substantially reinforce the role of hunting and gathering as ethical practices for our species, and the relevance of these activities to the inherited emotional and spiritual attachments we feel towards nature.

I acknowledge, in this effort, my desire to encourage, on a wider scale, the relationships between people and nature that I so admire in my own culture. But such relationships are ancient and real. They bring increased value to life and a greater sense of awareness of why the natural world matters. To those who might own land, such awareness can be a gift of inestimable value. It can be the gateway journey to a life in conservation.

Find Out More

Conservation Visions Inc.

PO Box 5489 – Stn C | 354 Water Street

St. John’s, Newfoundland A1C 5W4

709.754.4780

Insights@ConservationVisions.com