This article is featured in the Summer 2025 issue of Texas LAND magazine. Click here to find out more.

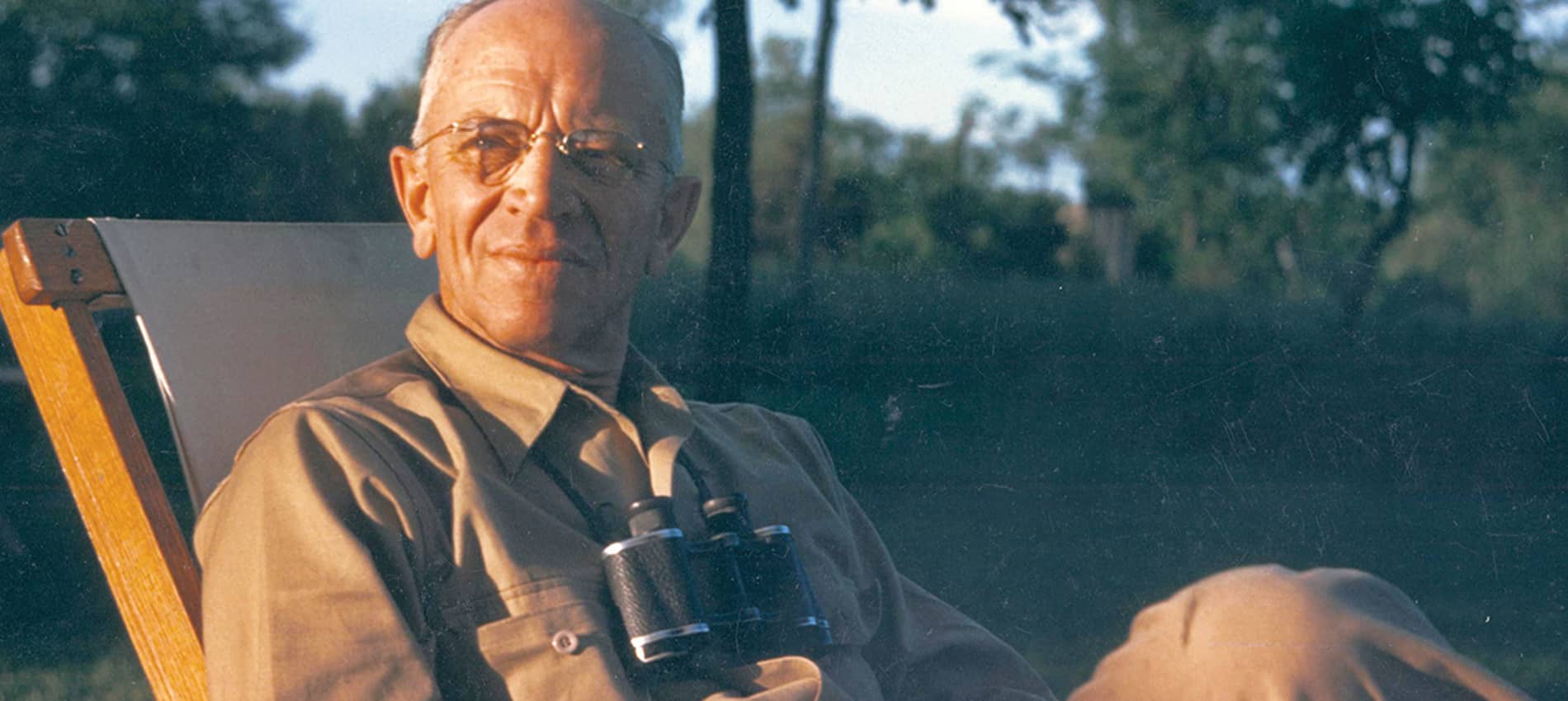

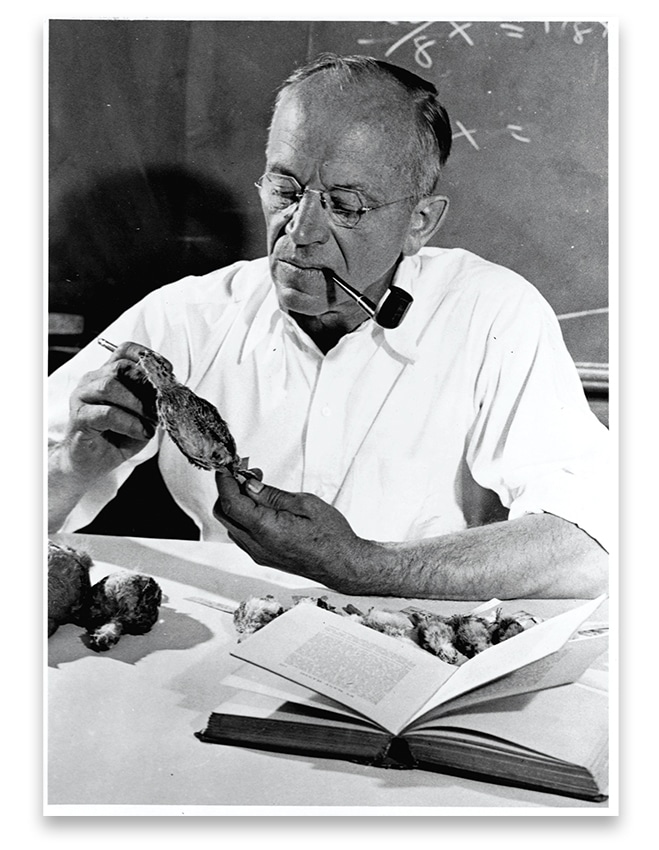

Known as the father of wildlife management, Aldo Leopold was a visionary conservationist and an accomplished writer whose ground-breaking ideas changed conservation in America—and continue to shape the landscape today. “A Sand County Almanac,” published in 1949 and widely considered Leopold’s masterwork, has sold more than 2 million copies world-wide and has been translated into 15 languages.

I sat down with Dr. Stanley “Stan” Temple, Beers-Bascom Professor in Conservation (emeritus) in the Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to discuss Leopold’s long-lasting influence.

In addition to being a globally recognized expert on birds and conservation ecology, Temple is also an expert on the life and work of Aldo Leopold. Not only is Temple the third individual to occupy the faculty position first held by Leopold, which was the first university position in the world dedicated to wildlife management, but he is also a director of the Sand County Foundation. The foundation, based in Madison, Wisconsin, is a non-profit organization dedicated to inspiring a land ethic and superlative land stewardship in private landowners across America.

As Temple said, “It is pretty amazing, isn’t it, that 75 years later Leopold’s ideas about our relationship with land have not grown old and seem to be as timely and stimulating as ever.”

He challenged people to examine each question in terms of what is ethically and aesthetically right as well as what is economically feasible or expedient.

1. As you consider Aldo Leopold’s life, what were some of the formative forces during his early years that set him on his journey of discovery and influence?

ST: He was born in 1887 and grew up while the modern conservation movement was a fledgling endeavor. Aldo was raised in a family that was part of this movement. His father Carl Leopold was an avid outdoorsman who encouraged his young son to embrace nature. As a hun ter, Carl was a great proponent of fair chase and ethical hunting, so as a boy Aldo was encouraged to have an ethical relationship with wildlife through hunting, which meant there was a right and wrong way to do it.

His father was also keenly aware of the conservation issues of the time, so Aldo would have been exposed to discussions about the tragic extinction of the Passenger Pigeon, the near extinction of American bison, and the decimation of wildlife populations caused by unregulated market hunting.

Early on Aldo knew he wanted to pursue a career in conservation. At the time, there was only one college degree in the field, so he studied forestry at Yale University. Upon graduation, he was immediately hired into the brand-new U.S. Forest Service and at 22-years-old was sent to New Mexico and Arizona, where he was responsible for surveying and managing millions of acres of wildlands.

Eventually, he grew to be at odds with his boss Gifford Pinchot on how to manage the land. Unlike Pinchot who maintained that National Forests should be managed primarily for the sustainable extraction of natural resources, Aldo advocated management practices that prioritized forest health, arguing that only if the forests were healthy could uses, like logging and grazing, be sustainable. It was the first time anyone had ever articulated what we today call ecosystem management. Interestingly, he espoused this in the early 1920s, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that the U.S. Forest Service adopted ecosystem management as the guiding principle for managing the National Forests.

2. Arguably, he is best known for writing the conservation classic, “A Sand County Almanac.” Why is this book considered his masterwork?

ST: By the time, he wrote “A Sand County Almanac,” Aldo had come to understand that conservation could only succeed by enlisting private landowners working on their own land.

Through various experiences, he had learned that regulations weren’t the most e ffective way to get people to do the righ t thing on their land nor were incentives, so his challenge was figuring out what might inspire conservation. He concluded it boiled do wn to ethics and people developing a moral compass about what is right and what is wrong in our relationship with the land.

In the 1930s and 40s, he penned a series of essays that trace the evolution of his thoughts about our relationship to the land that culminated in “A Sand County Almanac.” He was a gifted writer who had a talent for explaining complicated ideas using language that common people would understand. For instance, describing an abused landscape, he called it “sick land,” which helped people understand the need to nurse it back to health just as they would heal their sick bodies.

In “A Sand County Almanac,” which also recounts his experiences bringing his own farm back to ecological health, Aldo describes the land ethic, doing the right thing for the land because it’s the right thing to do, not because you are forced to by regulations or coerced by economic incentives and subsidies. He was the first to clearly articulate that idea—and this notion fundamentally changed the way many private landowners viewed their land.

3. Outside of the land ethic, what are some of Aldo Leopold’s other contributions that changed American conservation?

ST: Each contribution is a story in itself. As a young forester, not only did he push for ecosystem management, but Aldo also recognized that some of areas within the National Forests were so pristine that they should be protected. In 1924, he almost single-handedly argued for the creation of the Gila Wilderness, the first designated wilderness area on public land. This pre-dated Congress’ Wilderness Act by 50 years.

As a researcher exploring declining wildlife populations in the Midwest, Aldo went against the conventional thinking that more legal protection would mean more wildlife. Instead, he observed that wildlife populations declined because their habitat had been destroyed and argued that the key to increasing wildlife populations was increasing and improving habitat. It was the basis of wildlife management.

Those insights were the inspiration for “Game Management,” the first-ever wildlife management textbook, in which he advocated taking a science-based, hands-on approach to improving wildlife populations by improving habitat. Then, thanks to an unprecedented job offer from the University of Wisconsin, in 1933, he became the founder and first professor of the first wildlife management degree program in the world.

As another example, working on 1,000 acres of retired farmland owned by the university and his o wn small farm on the Wisconsin River, Aldo pioneered what we now call ecological restoration.

When he died of a heart attack at age 61, Aldo was arguably at the height of his intellectual powers and productivity. It makes one wonder what else he might have accomplished if he had lived longer.

4. What is the quote that you believe best reflects his philosophy of land management?

ST: When most people quote Aldo Leopold, it is often a line from “A Sand County Almanac” that is his very simple expression of the land ethic.

He wrote, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

It’s a maxim that can be used to test all human interactions with nature. Will the action conserve the health of the land or not? He challenged people to examine each question in terms of what is ethically and aesthetically right as well as what is economically feasible or expedient.

5. What is the Sand County Foundation and what does it do to keep Aldo Leopold’s legacy alive?

ST: The Sand County Foundation was created in 1967 by Reed Coleman, whose father was Aldo’s close friend and hunting buddy who owned the farm next to Aldo’s on the Wisconsin River. When Reed returned from college and visited the family farm after Aldo’s death, he was shocked to see that surrounding farms were being subdivided into small parcels and sold for vacation cabins.

Growing up indoctrinated by Aldo’s land ethic, Reed was horrified that Aldo’s carefully restored land was going to be surrounded by vacation homes. In 1965, Reed came up with a brilliant idea, which was probably the first-ever conservation land trust.

He went to the surrounding landowners in the area, only 17 years after Aldo died, and encouraged them to follow Aldo’s ideas about land stewardship, with which they were all familiar, and voluntarily agree to do the righ t thing on their land. He also asked them to give the other area landowners the first chance to buy their land if they ever chose to sell. The resulting landscape became the Leopold Memorial Reserve.

Recognizing that three-quarters of land in the contiguous states is privately owned and 85 percent of that is productive working lands like farms, ranches and forests, Sand County Foundation promotes a land ethic as a guide for private landowners nationwide. The foundation does this through several programs focused on improving land health on private working lands, the most visible of which is the Leopold Conservation Award. These prestigious awards recognize exemplary landowners who have demonstrated a land ethic on their property. Their stories inform and inspire other landowners to consider conservation on their land.

For more information, check out the following online resource:

Aldo Leopold and the Sand County Foundation