Considered by many to be the foremost representational landscape painter of our time, Clyde Aspevig’s personal and artistic horizons have unfolded expansively since his childhood on a Montana farm near the Canadian border. That period of geographical and cultural isolation was in retrospect a blessing for the artist he recalls. “Because I grew up in a vacuum in Montana, I wasn’t taught the cliches.”

He sees such naivete as allowing him to be more open to everything around him, which is especially evident in his latest works. His peripatetic field easel now ranges across the wild mountains and prairies of Montana, Death Valley, Adirondacks, rocky North Atlantic coast, Scandinavian fjords and the well-tended hillside estates of Tuscany. Growing up, he witnessed the alternatingly painful and joyful cycles of agricultural life. He was unusually fortunate to be encouraged by his family in the pursuits of art and appreciation of music. Clyde learned early on to work hard and persevere against obstacles natural and manmade. Rather than scoffing at or demeaning Clyde’s interests, Clyde’s father, the practical but open-minded farmer, bought his twelve-year-old son’s first painting.

He sees such naivete as allowing him to be more open to everything around him, which is especially evident in his latest works. His peripatetic field easel now ranges across the wild mountains and prairies of Montana, Death Valley, Adirondacks, rocky North Atlantic coast, Scandinavian fjords and the well-tended hillside estates of Tuscany. Growing up, he witnessed the alternatingly painful and joyful cycles of agricultural life. He was unusually fortunate to be encouraged by his family in the pursuits of art and appreciation of music. Clyde learned early on to work hard and persevere against obstacles natural and manmade. Rather than scoffing at or demeaning Clyde’s interests, Clyde’s father, the practical but open-minded farmer, bought his twelve-year-old son’s first painting.

He considers his paintings as old friends and visual souvenirs of places experienced in his life. The viewer, too, shares in Clyde’s magical evocations of the landscapes that touched him.

“I see nature as being so much more powerful than we realize.”

While his early efforts attracted awards and critical praise from the regional or “Western” sector of the art community, Clyde’s work has since emerged to be highly sought after by world class collectors. In a culture notorious for nourishing illustration of stereotypical, iconic subject matter, Clyde fearlessly departed whenever he felt the call, and resisted early attempts by Western art dealers to label him and restrict him to the saleable panoramic scenics.

His paintings of the West are not theatrical sets intended to reinforce regional mythology, but rather evocations of places that he perceives as already disappearing during his own lifetime, subjects worthy of both artistic and societal preservation.

I have been in many of these storms over the years and they never fail to excite. All of your senses are engaged. These storms can be beautiful and scary at the same time. Which is what we call the sublime.

The paintings reflect Clyde’s intense days of absorbing his natural surroundings, days which shaped a philosophy: “I see nature as being so much more powerful than we realize.” He sees the true value of preserving the last islands of wilderness, agreeing with the late writer Wallace Stegner that just the fact of knowing it is out there is important to the human spirit.

To Clyde Aspevig, painting expresses human emotion better than any other medium. The divine nature of light reveals to the receptive eye the timeless interaction of land forms and sky, water, flora, soil and rock. If he has any “mission” beyond the canvas in his creative endeavors, it is simply a wish to call attention to the timeless, intrinsic worth of our natural environment.

The image resolves from a deliberative yet intuitive process of the artist, seeing. Nature, undistorted by the filters of acculturation.

While hiking last spring, I came upon these fragrantly beautiful wild plum trees. I had to paint them in their springtime display of blossoms.

Clyde’s intent is to create something beautiful and harmonic. While subject matter is of prime consideration, further contemplation of the painting eventually yields its subtle nuances of texture and rhythm. His paintings possess qualities meant to outlast the viewer’s initial infatuation, qualities that will endure well into succeeding generations.

Each painting is a struggle and a journey for the artist, the destination a prolonged feast of discovery for the viewer. While his mastery of the medium is apparent, the desire of the artist is that technique shall never override the painting’s essential concept.

His own physical and spiritual connection with the subject’s place and time emerges on the canvas, a transformation intended to be savored as long as the work exists. As far as Clyde is concerned, some of the most powerful representations he developed were those that left something out. That the viewer notices a sense of space, rhythm and harmony is no accident.

“Paintings become symbols of all that we are.”

All the while, there is the composer, with brush and palette knife, conducting, refining, coaxing, interpreting his own score. As he explains, “I use music all the time in my paintings.” The discerning viewer sees and feels the brushstrokes corresponding to musical notes and movements—legatos broad and delicate, an adagio of cured prairie grasses, a swirling vivace of light and clouds over the marcato of mountain granite. Clyde’s music touches the eyes with distinct rhythmic textures, letting the canvas reflect how earth and sky are interwoven. The result is the artist’s ethereal yet tactile manifestation of natural forces: “Paintings become symbols of all that we are.”

Clyde Aspevig is acutely conscious of the forces constantly at work sculpting the earth; erosion from rain and melting snow, wind, extremes of heat and cold. While the evidence so far suggests that the earth has endured millennia of human folly, he is aware of the fragility of life and how industrialized civilization has so rapidly altered entire mountains and rivers and displaced ancient buffalo ranges and forests.

And yet the artist moves on, seeing, feeling, preserving on canvas what is best that remains of the New World, while absorbing excellence from masters of the Old World. If we, too, allow ourselves to look carefully, we may all become a little richer.

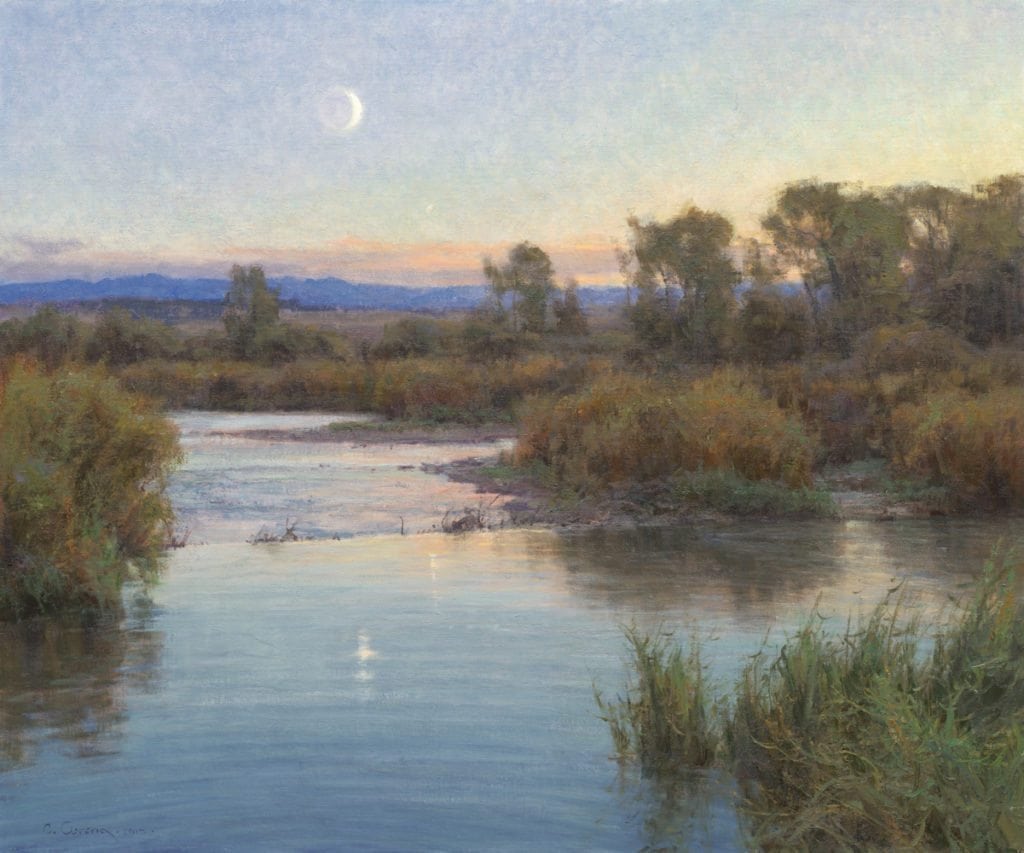

Planetary Alignment & What the Beaver Knows,” a 30” x 36” oil, is the result of what Clyde refers to as “one of my creative adventures.” Of it, he says: “Around the 12th of September the crescent moon and the planet Mercury appear in the horizon at dusk. This particular evening I walked down to the beaver dam in front of our house to watch the activity of a family of beavers. As soon as I arrived, the parents slapped their tails to warn the youngsters. The kits dove away from the perceived danger. I then made a gentle splash with my hand, making ripples on the water, which moved across the pond. The male beaver, sensing this disruption, surfaced to challenge the intruder. He circled the pond making sure his domain and family were safe. Between the moon, the planet and the beavers, I considered the immensity of the moment.

These old Juniper Tree posts remind me of many of the people I grew up with in Northern Montana. There is a distinct character about each one of us. Time may wear us down but there is a beauty in the nobility of how we persist.

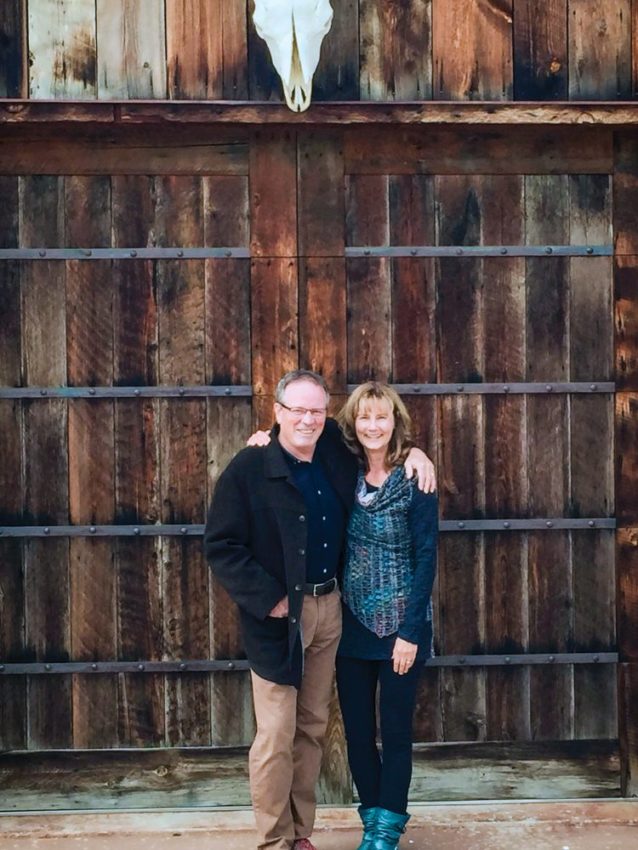

EDITOR’S NOTE: I had the distinct pleasure of meeting Clyde and his lovely artist wife, Carol Guzman, at their home in Clyde Park, Montana this past October. Our visit was captivating and inspiring. Clyde and Carol were so gracious in opening up their home and their studios, and in sharing a little piece of themselves with us, which I will carry with me in my soul for years to come. Find out more about Clyde and see more of his extraordinary work by visiting clydeaspevig.com.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2015 Issue of LAND Magazine, a Lands of America print publication. Subscribe here today!