La Panza, now a ghost town located in the La Panza mountain range in San Luis Obispo County, was once the site of California’s only Coast Range gold rush.

The name La Panza can be traced back to the early days of Spanish and Mexican settlement when the area was known as prime territory for Ursus horribilis, the now-extinct California grizzly bear. Vaqueros intent on protecting their livestock often used bits of slaughtered cattle, including “the paunch,” to lure bears, so they could be poisoned, trapped or lassoed.

Some of the bears may have been caught and kept alive. In the late 19th century in frontier California, promoters pitted captured bears against full-grown bulls in a public fight to the death.

While California’s legendary Gold Rush took place from 1848–1855, the La Panza gold rush made its historical mark beginning in 1878. According to the accepted mix of legend, lore and fact, a failed mule deer hunt led to the discovery of gold.

Needing to refill his larder, Efranio Trujillo mounted his horse and left his camp in search of a deer. A day of hard riding finally brought him success in the form of a young buck with barely emerged antlers. When Trujillo fired, he wounded the animal, which bounded away.

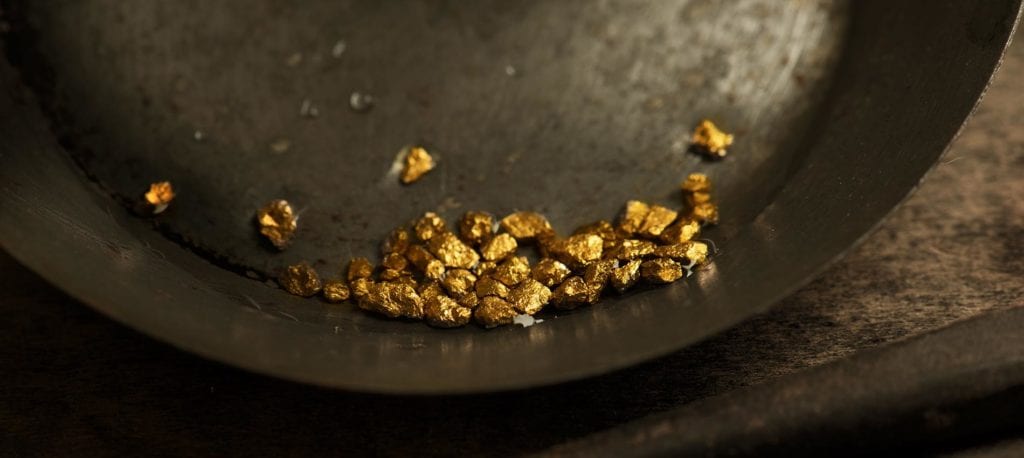

Trujillo trailed the injured animal until he lost the tracks and realized the animal’s wound wasn’t life threatening. Disgruntled he stopped at a spring to rest his horse and belatedly eat his lunch. As he bent toward the refreshing water, he saw a glittering sandbar. In that mixture of sand and precious metal, Trujillo spotted gold flakes, two or three of which were large enough to pick up by hand.

Strictly speaking, though, Trujillo’s discovery was no discovery at all. The mission padres had known of gold in the La Panza hills and had Native American neophytes likely from the Chumash tribe mining there in the early 1800s. In the 1830s when secularization of the missions had taken over Church property in California, the padres had closed the mines and sworn the Native Americans to secrecy.

No one swore Trujillo to secrecy, and as word of the “flakes big enough to pick up by hand” spread, the once isolated tributary of the San Juan River boomed and a boisterous mining camp was formed, complete with a saloon and dance hall. Within the next few weeks, between 500 and 600 men stampeded into the area hoping to strike it rich. The area would become one of the most important California gold fields outside the Mother Lode country.

In the spring of 1879, word of the mining excitement reached Dr. Thomas C. Still, a medical practitioner from Kern County. He moved his family to the mining field. Still not only hauled and sold produce to the mining camp, he established a general store and applied for a post office permit. In November of that year, the La Panza Post Office was established.

The post office was named after the nearby La Panza Ranch, which had been owned in the 1860s by Drury James, uncle of outlaws Frank and Jesse. According to stories, the duo, under false names, holed up at the ranch for a time. Their ruse didn’t fool the locals.

By the time gold fever hit the area, the ranch, which was adjacent to the gold field, had been sold to the partnership of Jones and Schoenfeld. They raised sheep and cattle.

Mining camps, with their mix of prospectors, drifters, grifters and outlaws, were a cauldron for mayhem. Fortunately for area residents, Dr. Still continued to practice medicine. Many decades later, Still’s grandson, O.M. Maclean, relayed one of the many episodes of frontier medicine.

One night Dr. Still was roused from his sleep by urgent, incessant knocking. When he opened the door, a man asked him to come treat a wounded friend.

In answer to the question of what happened, the excited man blurted out, “I shot a man.” He caught his error and quickly said, “I mean, a man has shot himself.”

Upon arriving at the wounded man’s bedside, the doctor determined the patient was in very grave condition. Despite his patient’s precarious hold on life, Dr. Still successfully removed the bullet. He instructed the patient’s friend that moving the injured man could prove fatal.

The next morning Dr. Still was greeted by an empty room. The two men, on the run from the law, had disappeared because they were afraid he would report the incident to the sheriff.

While La Panza generated a lot of excitement, it was not an easy field to work. Many of the streams were small and intermittent.

An anonymous miner who prospected in the area published an account in the South Coast newspaper on February 5, 1879. He wrote: “Prospects of fine gold are found nearly everywhere in the streams. Evidently there are rich pockets of gold which wash into the streams and lower flats, but there is not enough water to use the hydraulic process.”

The first official report of gold production was made in 1882 when $5,000 was reportedly taken out. By 1886, the region was producing $9,164 a year, which proved to be its largest recorded annual take, but it dropped to $1,740 in 1887. The numbers continued to rise and fall each year, with the lowest annual recovery of $124 occurring in 1913, the last available report.

While there was never a huge strike, it is estimated the La Panza region produced at least $100,000 worth of the precious metal. In comparison, the Sacramento Valley, which is home to Sutter’s Mill and the ensuing Mother Lode strikes, produced more than $2 billion worth of gold from 1848–1852.

As gold production subsided, so did gold fever and the area’s population. Quiet returned to the region as did deer, mountain lions, coyotes and ranching.

A Snapshot of San Luis Obispo County

San Luis Obispo County, locally known as SLO County, is located along the Pacific Ocean in Central California between Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay area. The county is one of California’s original counties, created in 1850 at the time of statehood. The county seat is San Luis Obispo.

Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa was founded on September 1, 1772 in the area that is now the city of San Luis Obispo. The mission, city and county were named for Saint Louis of Toulouse, who was the young bishop of Toulouse in 1297. Obispo means bishop in Spanish, while Tolosa is the Spanish spelling of Toulouse.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 3,616 square miles, of which 3,299 square miles is land and 317 square miles is water. In 2017, the population was 283,409.

The county’s communities are relatively small and scattered along the beaches, coastal hills and mountains of the Santa Lucia range. The diverse ecosystems support many kinds of fishing, agriculture and tourism.

San Luis Obispo County is the third largest producer of wine in California, surpassed only by Sonoma and Napa counties. After strawberries, wine grapes are the county’s second largest agricultural crop. Wine production creates a direct economic impact as well as supporting a burgeoning wine country tourism industry. In addition, California Polytechnic State University with its almost 20,000 students is a major economic engine.

The town of San Simeon is located at the foot of the ridge where newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst built Hearst Castle. Other coastal towns from north to south include Cambria, Cayucos, Morro Bay and Los Osos-Baywood Park. These cities and villages are located northwest of San Luis Obispo city and Avila Beach. The Five Cities region, which consists of Pismo Beach, Grover Beach and Oceano (County), is located to the south. Nipomo, just south of the Five Cities, borders northern Santa Barbara County.

Inland, the cities of Paso Robles, Templeton and Atascadero lie along the Salinas River, near the Paso Robles wine region. The Salinas River Valley, a region that figures strongly in several John Steinbeck novels, stretches north from San Luis Obispo County.

The remote California Valley near Soda Lake is the region’s least developed area. Travels through this area and the hills east of Highway 101 during wildflower season are very beautiful, and many people incorporate wildflower viewing with wine tasting at local vineyards.