The Elk Mountain Grand Traverse is an annual endurance ski race starting in Crested Butte, Colorado, at midnight, finishing in Aspen the next day. In this extreme endurance event, racers will travel 40-plus miles, climb more than 7,800 vertical feet, and navigate in a self-supported backcountry race that tests them physically and mentally. To maintain safety in the backcountry, racers compete in teams of two and are required to carry mandatory gear. Held annually since 1998, it has earned a reputation as a true test of toughness for elite local, national, and international athletes.

I moved my family from Dallas to Crested Butte in 2009, and shortly thereafter my brother and I decided we wanted to compete in the Grand Traverse. Our team name was “Kopf Brothers”—Chris Kopf and Rick Kopf. In comparison to the other racers, we were the old guy rookie team (I was 50 and Rick was 56). Our stated goals were:

Do not die.

Finish.

Don’t be last.

Of course our wives and friends said we were nuts.

We did not know what we did not know. There were hundreds of details and questions about equipment, navigation, and safety, but weighing heaviest on our minds was whether a prolonged stop would introduce hypothermia and frostbite? As one advisor told us, “You really don’t understand this race until you finish.”

We did not know what we did not know. There were hundreds of details and questions about equipment, navigation, and safety, but weighing heaviest on our minds was whether a prolonged stop would introduce hypothermia and frostbite? As one advisor told us, “You really don’t understand this race until you finish.”

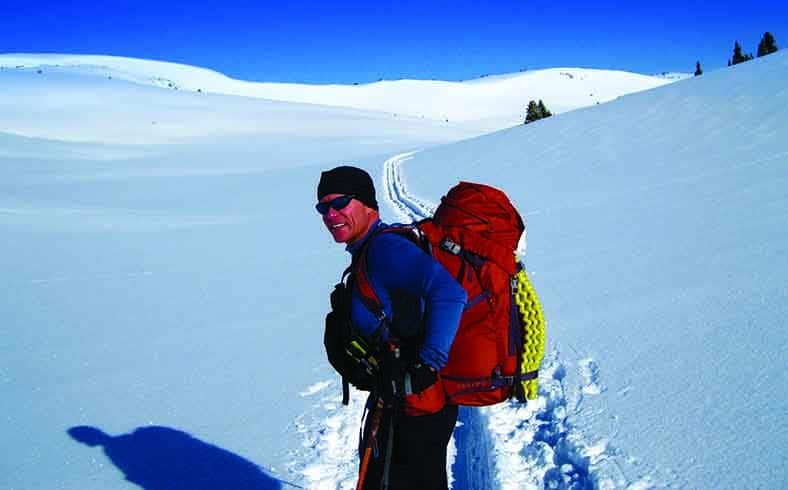

We had completed the Texas Water Safari, which was a 260-mile canoe race, but this was much different given the risk of avalanche danger and extreme cold. We are expert downhill skiers but had very little backcountry skiing and winter survival experience. The fear of the unknown was a strong motivator, and we knew that to support each other and finish we needed to be in great physical condition. We trained on average 90 minutes per day, six days per week for nearly, five months prior to the race. My training was mostly solo uphill climbing on skis in the dark. Rick lived and trained mainly in Dallas—mostly on a stair machine and on roller skis (yes, roller skis).

On race day there was a storm, which increased the avalanche danger at Death Pass and Star Pass. We said a brief prayer prior to the race start. The gun sounded at midnight, and we were off…

We climbed up and over Mt. Crested Butte before starting the long march up Brush Creek toward Star Pass. If we did not make it to Star Pass by 8 a.m., we would be turned around.

Arrival, Death Pass: 3 a.m. I had a huge blister on my left heel; I stopped and used duct tape as a bandage—a mistake because soon I had a wad of duct tape rubbing against the blister.

Death Pass is aptly named, because there is a traverse across a very steep avalanche slide area with ice chunks, trees, and rocks above a cliff and rushing icy water below.

Checkpoint two is the Friends Hut, and when we arrived at 6:15 a.m. our fingers and toes were frozen. Our vision of a warm friendly checkpoint with a hut to rest in quickly vanished: There was no hut, it was cold, and we were exposed to high winds. With no reason to stay and shiver, we pushed on. The climb was steep and endless.

Life Lesson: The top is only a place from which you can see the next peak.

At one point, we saw that a racer had slid fifty yards below the traverse line and was struggling to climb back up. To avoid the same fate, we searched for the smallest cuts in the ice to hold the edge of our skis.

Star Pass summit: 7:15 a.m. The beautiful sunrise was worth the effort. We were less than half way, but we would not be turned back!

Skiing down the steep backside of Star Pass through deep snow was very difficult on skinny skis with heavy packs. We fell multiple times, and it took great effort to get back up.

At the Taylor Pass checkpoint, we enthusiastically asked the race officials, “which way down?” They held back their laughter and pointed to the top of the next peak and said: “Sorry, you still have to climb to the top of that peak . . . but then it is all downhill from there.”

Life Lesson: It is never “all downhill from there.”

At the Barnard Hut checkpoint, there was a mandatory rest and inspection by a doctor. The blister on my heel was screaming, but I chose not to mention it for fear I would be forced to withdraw. We were given hot soup, warm Gu, and cold pizza.

We were told we had seven “quick and flat” miles to the Aspen Sun deck. Instead, it was brutally long, constantly up hill, and mentally tiring. We motivated each other to keep pushing.

We envisioned the Sun Deck as a mountain restaurant crowded with well-wishers, music, and cheering . . . NOT! There were three race officials with clipboards.

The final 3,300 feet from the Sun Deck to the base area was downhill, but hard, as our packs were heavy and our legs were spent.

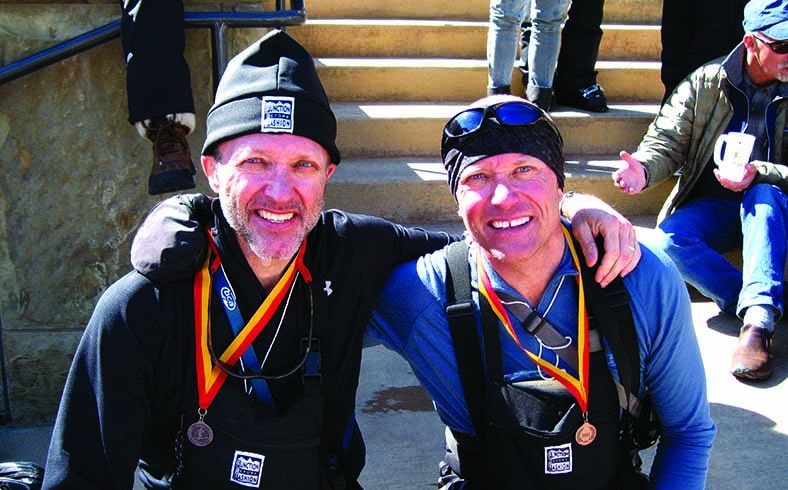

We stopped at the top of the last hill and now looked down at the finish. We had made it! There was a crowd, there was cheering, and they announced our names over the loudspeaker, “Here come the Kopf Brothers!”

After five months of preparation and very hard training, we had done it—we had arrived at the finish! The weight of the moment hit us. We shed tears of joy.

Rick looked at me and said: “I couldn’t have done it without you!” Looking back, I replied: “I wouldn’t have done it without you!”

Our official time was 15 hours, four minutes, and 25 seconds. We are among an elite group who has finished.

We lacked knowledge and experience, but we succeeded because we had the will. We put a plan in place, we did not quit, and we achieved our goal.