Land brokers and real estate agents, among others in Texas, have witnessed first-hand the positive economic impacts of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking), which make it possible for producers to tap vast deposits of natural gas and oil trapped in tight sand and shale formations. Builders work day and night to construct enough homes and hotels to house production people moving into Texas communities. Restaurants stay full 24 hours a day and retailers enjoy high cash flows. Many landowners receive monthly royalty checks that enhance life styles at a higher plane than they have previously experienced. Increased tax payments by the oil companies have added to the state coffers as well. The downside of the economic bonanza is that roads are being pulverized by heavy trucks constantly moving equipment and products and utilities and other infrastructures are strained by the sudden population growth.

As this article is being written, the oil industry is in a cooling period with depressed pricing and reduced drilling activity. On April 10, West Texas Intermediate crude oil was reported at $51.64 per barrel by Baker-Hughes. A year ago on April 10, the price was $103.40 per barrel. The U.S. rig count on April 10 was 843 less than a year ago due to the drop in oil prices.

When an activity draws as much attention as fracking, people begin to look for negative impacts, particularly when they are not directly benefiting from the development. Groups have formed to oppose fracking based on several concerns and some are justifiable. One of the primary concerns is depletion of our ever shrinking water supplies. A huge amount of information on water usage in fracking has been distributed, some of it is factual. A correct resolution of any issue can only be obtained with facts delivered by qualified experts on the subject. Often the truth is masked by pseudo experts making the most noise. So, what is the true story of water usage in hydraulic fracturing?

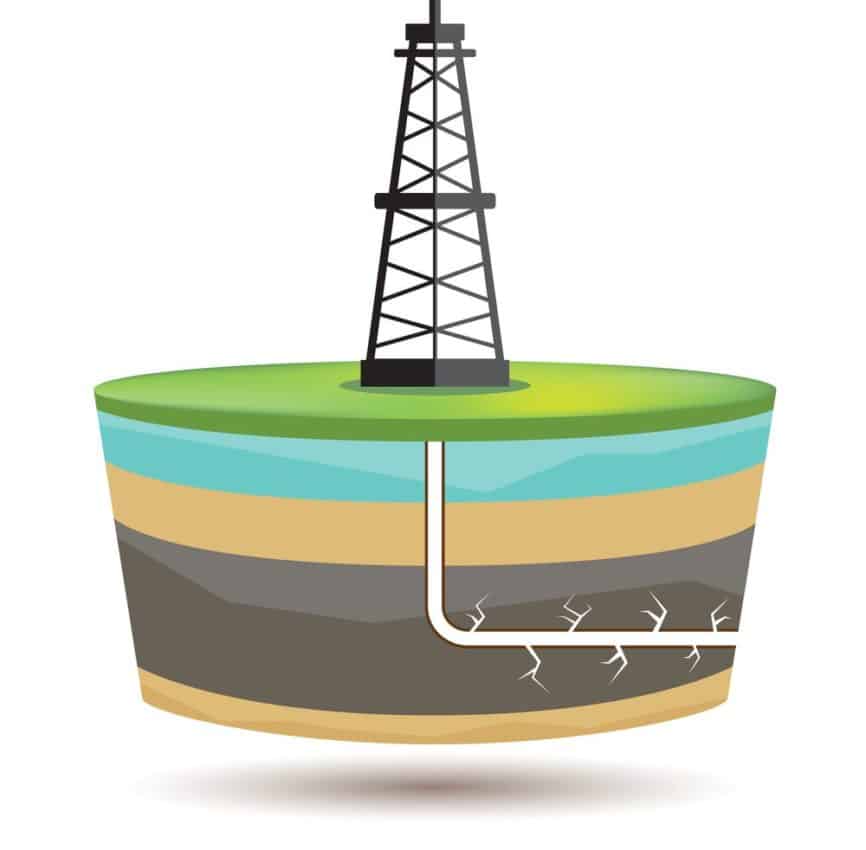

Michael MacRae, an independent writer, prepared the following history for the American Society of Mechanical Engineers: “The mechanical principles of fracking have not changed since the first brave shooter dropped an explosive charge down a well in the 1860s. Then as now, the task is to deliver a powerful force to a designated underground depth, fracturing rock formations around the well to stimulate release of trapped oil or gas.”

Modern methods of fracturing use high-pressure jets of water and sand to break up shale formations. Water rushes into the newly-opened pore space during fracking and carries sand deep into the rock formation. Sand holds the fractures open and allows a flow of oil or natural gas, even when the pump is turned off and water pressure is reduced.

“The first use of hydraulic fracturing in oil and natural gas wells in the United States was done over 60 years ago,” Hobart King wrote for Geology.com. “Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Company was issued a patent for the procedure in 1949. The method successfully increased well production rates and the practice quickly spread. It is now used throughout the world in thousands of wells every year.”

WATER USAGE IN PERSPECTIVE

“A typical early fracture took 750 gallons of fluid (water, gelled crude oil, or gelled kerosene) and 400 pounds of sand,” said MacRae. “By contrast, modern methods can use up to eight million gallons of water and 75,000–320,000 pounds of sand. Fracking fluids can take the form of foams, gels, or slick water combinations (water plus chemicals). The chemicals often include benzene, hydrochloric acid, friction reducers, guar gum, biocides and diesel fuel.”

According to Chesapeake Energy, an initial drilling operation may require from 6,000–600,000 gallons of fracking fluids of which water is the largest component. Water and sand can be more than 99.5 percent of the fracturing fluid with one-half percent chemicals or less. Chesapeake says that an additional five million gallons may be required for full operation and possible re-stimulation frack jobs. These quantities seen huge, but they are small when compared to other water uses within the state.

“Texas uses about 711 million gallons of water each day with 60 percent going to agriculture, 15 percent to industry and 25 percent directly to the state’s citizens,” estimates the Water Development Board. “Mining, including oil and gas production, is one to two percent of the state’s total water use.”

A 2013 study, completed by The University of Texas – Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology, shows that the amount of water used in hydraulic fracturing has increased sharply in recent years due to the surge of oil and natural gas production. In this study, funded by the Texas Oil and Gas Association, it was found that total water use for fracking in Texas rose by about 125 percent, from 36,000 acre-feet in 2008 to about 81,500 acre-feet in 2011. For comparison, the city of Austin used approximately 107,000 acre-feet of water in 2011. About one-fifth of the current total amount used in fracking comes from recycled or brackish water, a category that is growing. It was also found in the study, that the amount of water used in fracking will level off sometime in the decade beginning in 2020, as the industry’s rapid growth rate cools and water recycling technologies mature.

TIME magazine reported on a University of Texas study that showed fracking for natural gas actually saves water by making it easier for utilities to switch from thirsty coal plants to more efficient natural gas power. Researchers collected water utilization data from all 423 of the state’s power plants to estimate the amount that can be saved by switching from coal to natural gas. Coal fired generation plants use 25–50 times more water than required for fracking to extract the shale gas. Their calculations also showed that Texas would have consumed an extra 32 billion gallons of water if all its natural gas-fired plants were burning coal instead.

“The bottom line is that our electric power system can become more drought resilient by boosting natural gas production with fracking and moving the state away from water-intensive coal technologies,” said Bridget Scanlon, senior research scientist at the University of Texas’ Bureau of Economic Geology and the lead author on the study.

Water conservation through recycling “The natural-gas industry uses a number of methods to recycle drilling waste, reports SourceWatch. “Some drillers use recycling equipment at the well site or truck the water to a recycling facility where the wastewater is filtered, evaporated and then distilled, to be used again for fracking. Other companies add fresh water to the wastewater, to dilute the salts and other contaminants, before pumping it back in the ground for hydro fracturing. Any fracking sludge from the various recycling processes is taken to landfills or is sent to injection disposal wells.”

Texas Railroad Commissioner Christi Craddick hosted a Texas Oil and Gas Water Conservation and Recycling Symposium in Austin during May of last year. At the symposium, industry representatives updated Commissioner Craddick and staff on industry best practices in water recycling and conservation and discussed future directions, challenges and opportunities to further save water. Twenty-six companies with recycling operations were represented, and 15 companies gave presentations on their recycling achievements.

The companies reported to-date recycling capacity of up to 1.5 million barrels of water per day. They have recycled up to 50 million barrels of water since industry focus to increase recycling began in 2012 and are using recycled produced water to account for up to 100 percent of their water needs in energy production. The amount of produced water hauled by trucking and disposed underground has decreased, and will continue to decrease exponentially. Produced water is now a resource and sold as a commodity for re-use in hydraulic fracturing operations.

There is a lot of good news on hydraulic fracturing while further concerns will be addressed with technology developed through research.