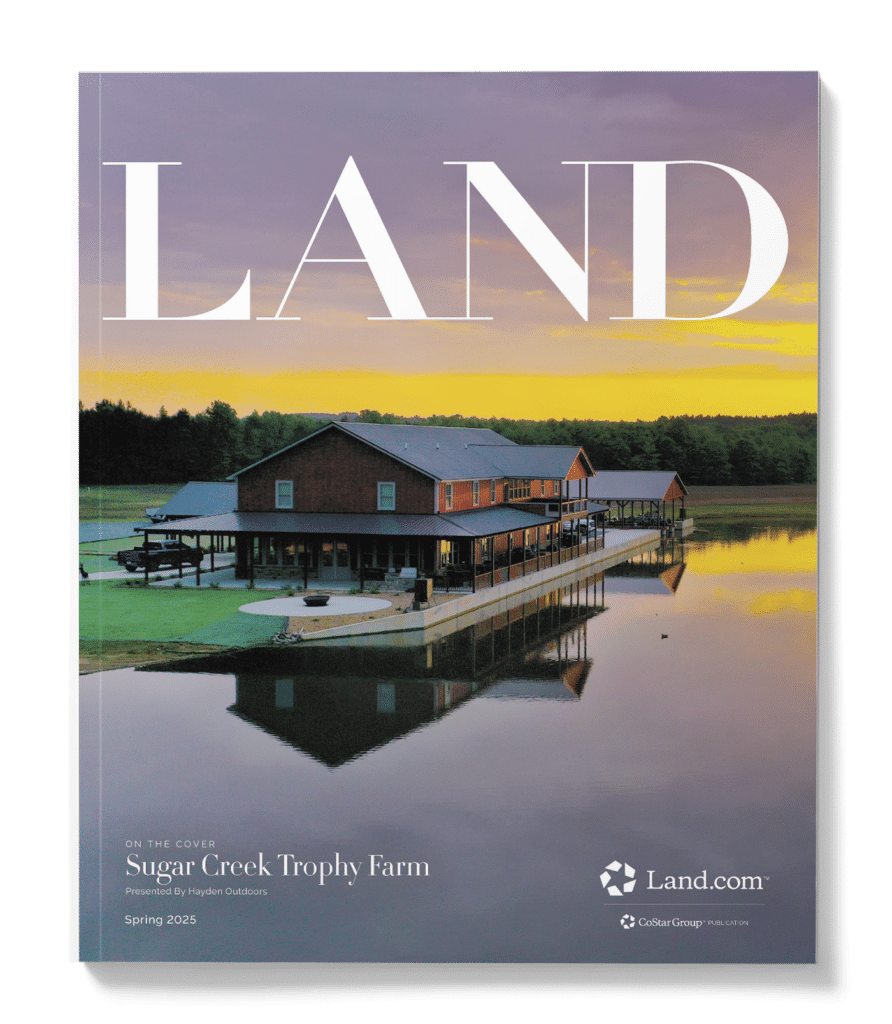

This article is featured in the Spring 2025 issue of LAND magazine. Click here to find out more.

Except for deserts, most North American ecosystems evolved with fire. Whether sparked by natural events such as lightning strikes or deliberately set by Native Americans to manipulate vegetation for agriculture, influence the movement of wildlife herds or other goals, fire shaped the landscape.

On the seemingly endless plains, fire, along with rest and rotation that occurred because of the constantly migrating herds of grazers, kept grasslands open, vibrant and relatively free of brush and trees. In the southeastern forests, periodic fire kept the forest floor open and grassy while maintaining those woodlands in an earlier successional stage. The plant community that thrived under those conditions provided the necessary habitat for the wildlife that evolved alongside them.

European landscapes and ecosystems responded differently to fire, so Europeans had a very different viewpoint of fire. When they immigrated to America, they brought their understanding with them and fire suppression became the overarching goal.

As time passed, the unintended consequences of no fire became evident on the landscape. Woody plants began encroaching on rangelands. The composition and age structure of forests changed. Fuel loads accumulated setting the stage for wildfires. Wildlife populations reflected changes in habitat.

While historically people had questioned the role of fire on the landscape, it was not until the 1980s that visionary range scientists began to study its impacts and advocate its use as a land management tool. Since that time, prescribed burning has been used to reinvigorate rangelands and forests.

I sat down with Dr. Sandra Rideout-Hanzak, Professor of Restoration and Fire Ecology at Texas A&M University-Kingsville and the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute in Kingsville, Texas, to discuss prescribed burning and the role of fire in the 21st century.

1. What is prescribed burning and why is this name more accurate than earlier names?

SR-H: When we are planning a prescribed fire, we are choosing the conditions under which we will set the fire in an attempt to create certain outcomes on the landscape. For instance, we choose an acceptable range for air temperature, humidity, wind speed, wind direction and soil moisture among many other things. All the conditions must fall within the parameters we have set before we will light the fire. We also identify what we will allow and things that are unacceptable within the context of the burn.

Just as a doctor writes a prescription for a patient to cure an illness, we write a prescription for the fire to help rejuvenate the landscape and bring it back to a healthier, more balanced state. Because we prescribe the conditions and the outcome, prescribed burning is the most accurate name to date. One earlier name was controlled burning. Truthfully, the only fires we control are the ones in our grill or fireplaces.

2. What role does fire play in the environment?

SR-H: We could spend an entire semester discussing this, but we’ll just hit the high points here. First, fire removes dead plant material and makes room for new plants. When that happens, we renew, refresh and restart the plant community. Livestock and wildlife, including birds and insects, respond.

Fire also releases nutrients bound up in the old growth, providing a temporary boost of fertility, especially in woodland environments.

Finally, a prescribed fire removes excess fuel. Even if it seems counterintuitive, planned fire is our best defense against uncontrolled wildfires.

As a side note, prescribed burning is one of the most cost-effective tools for managing brush on rangelands. It’s not necessarily easy, but with planning it’s useful.

3. Since fire was once an integral part of North American landscapes, how has widespread fire suppression impacted the environment?

SR-H: Fire sets back succession, the natural replacement of one plant community with another. It usually follows this order: small plants such as grasses give way to shrubs and then trees. Those trees may change type and species over hundreds or thousands of years.

With the suppression of fire, we lost the primary force that stopped or slowed succession. As a result, grasslands are becoming more forested with the encroachment of juniper, mesquite and other woody plants. We have lost some of the early successional forests as they have moved into older successional stages.

In the Eastern forests, there’s a very interesting phenomenon called mesophication. Through mesophication caused by the absence of fire, drier and more flammable systems have become more humid, shadier and more jungle-like. As a result, it’s even harder to get a fire started to begin to clear out that dense undergrowth.

When the vegetation changes like it does through mesophication, so does the wildlife. For instance, wild bobwhite quail used to abound in the southeastern pine forests and that’s no longer the case. The forest floors used to be grassier and more open than they are now, and the bobwhite need grassland habitat.

4. How does a wildfire differ from a prescribed burn?

SR-H: The biggest difference between a wildfire and a prescribed burn is the conditions under which they occur. In general, wildfires usually occur when a rainy period that grows a lot of vegetation gives way to a dry period or drought. The vegetation dries out, dies and becomes fuel. Then, on a random day the wind starts to howl, the humidity is low, a spark happens and a wildfire roars to life and uncontrollably runs over the landscape. It burns intensely and behaves erratically, leaving bare ground and oftentimes severely damaged plant roots in its wake.

We would never light a prescribed fire under those conditions. We would never stress those plants that are already struggling from drought by burning them. For a prescribed burn, we would ensure that there was enough soil moisture available for the plants to bounce back from the burn.

A wildfire is not necessarily hotter than a prescribed fire, but it is damaging to the plants and the soil under the conditions that they were subjected to the fire.

Just as a doctor writes a prescription for a patient to cure an illness, we write a prescription for the fire to help rejuvenate the landscape and bring it back to a healthier, more balanced state.

5. What steps are necessary preparing for a prescribed burn?

SR-H: Planning, planning and more planning. Sometimes this process can take a year or two. Patience is necessary.

First, identify the parcel you want to burn and identify the goals you have for that property, so you can set up the parameters that are pertinent for the burn.

Put your plans in writing. It’s not enough to have it in your head. Your plan will include everything from the specified weather conditions, the firelines and necessary equipment to emergency contact information and the number of people necessary to complete the burn.

Recruit your crew of helpers including a certified burn boss. The number of people necessary to complete each burn depends on the size and shape of the burn unit, the fuel type and the terrain.

You also have to lay in your firelines, which are fire breaks. They can be natural breaks such as dry canyons and sand dunes or lines that you create using equipment to scrape down to the mineral soils. Because the mineral lines are often the last remaining signs of the burn, we really try to minimize their use through creativity and using natural breaks or existing roads.

It’s important to notify your sheriff’s department and your neighbors prior to the burn. On the day of the burn, they need to be aware that the burn is planned and not

a wildfire.

When the day of the burn arrives, you must review the conditions objectively. If the conditions don’t meet the prescription and fall beyond the parameters for a safe, effective burn, you have to be prepared to postpone the burn until a day the conditions can be met. After all the work and waiting, being forced to say “no go today” is hard, but it’s necessary to protect the landscape and the lives of the people involved in the burn.

FOR MORE INFORMATION CHECK OUT THE FOLLOWING ONLINE RESOURCES: