Stephen J. “Tio” Kleberg is a cowboy by nature and a rancher by nurture. “When most kids are in elementary school, they aspire to be firemen or doctors or policemen, but I always wanted to be a cowboy,” Kleberg, who represents the fifth generation to have lived and worked on King Ranch, said.

Kleberg began working on the ranch when he was nine. By the time he was 11, Kleberg was riding with the vaqueros. An aunt raised his ire when she told him he’d better learn to be more than “just a cowboy.” “I took great offense,” Kleberg, who was reared on the ranch from birth until he left to attend high school at the Texas Military Institute in San Antonio, recalled. “I thought she was disparaging my dream.

It took some maturity and experience for Kleberg to recognize the intricate connection between the land, the cattle, the horses, the wildlife, the grasses, the water, the ecosystem and the business—and to understand what the wise woman meant.

“She knew that managing a ranch well in the present—and for the future—took a lot more than riding horses and working cattle every day,” Kleberg said.

Land is nothing but a piece of dirt. You—and the people who work alongside you—make the difference.

Her observation shaped his career. Other than a two-year stint in the army, Kleberg dedicated his professional life to the historic 825,000-acre South Texas ranch. In 1971, he came home to manage the ranch’s cattle, horse and farming operations. As his experience grew, so did his responsibilities. He eventually served as Vice-President of Agri-Business with operations in Texas, Florida, Arizona, Argentina and Brazil until 1998 when he joined the board of directors, a position he still holds today.

“Other than what I learned at college studying animal science and business, my father taught me most of what I know through hard work and discipline,” Kleberg, a 1969 graduate of Texas Tech, said.

Through legacy and by example, Kleberg learned what, perhaps, was his most important lesson: the land and the people who work it are an indivisible unit.

“Land is nothing but a piece of dirt,” he said. “You—and the people who work alongside you—make the difference.”

“Land is nothing but a piece of dirt,” he said. “You—and the people who work alongside you—make the difference.”

At the height of a great drought, Capt. Richard King, the ranch’s founder, traveled to Cruillas, Mexico where the townspeople not only sold him all of their cattle, but many moved north with him to work on the ranch. They and the succeeding generations of their families became known as Los Kineños, the King’s men.

“I knew the people well and through them I learned the land well,” Kleberg said. “Walking across it, driving across it and riding across it, I saw the land from the vantage point of cowboys, fence crews, wildlife biologists, livestock managers as well as attorneys, executives, oil and gas men and my family. It was a process of osmosis.”

Of course, knowledge is useless until it’s applied.

“As a manager, you will make mistakes,” Kleberg said. “Learn from them. Don’t repeat them. Move forward.”

Wildlife

As much as Kleberg enjoys raising superior cattle and horses, those activities are lumped into the category of work. Wildlife, conservation and hunting are passions.

“I dream about hunting,” Kleberg, a long-time member of the Texas Wildlife Association, said. “If someone said, ‘Tio, you only have three days to live,’ I’d spend them behind a good bird dog hunting wild bobwhite quail.”

He got his start hunting alongside his grandfather Richard Sr., his father Richard Jr. known as Dick, and Walter Sandifer, a self-taught expert on South Texas quail who was in charge of training and handling the bird dogs.

“Walter knew as much as any Ph.D. and he learned it by being on the land every day and paying attention to what was going on,” Kleberg said. “As a kid, I spent days trailing along with Walter soaking up everything I could as he trained English Pointers.”

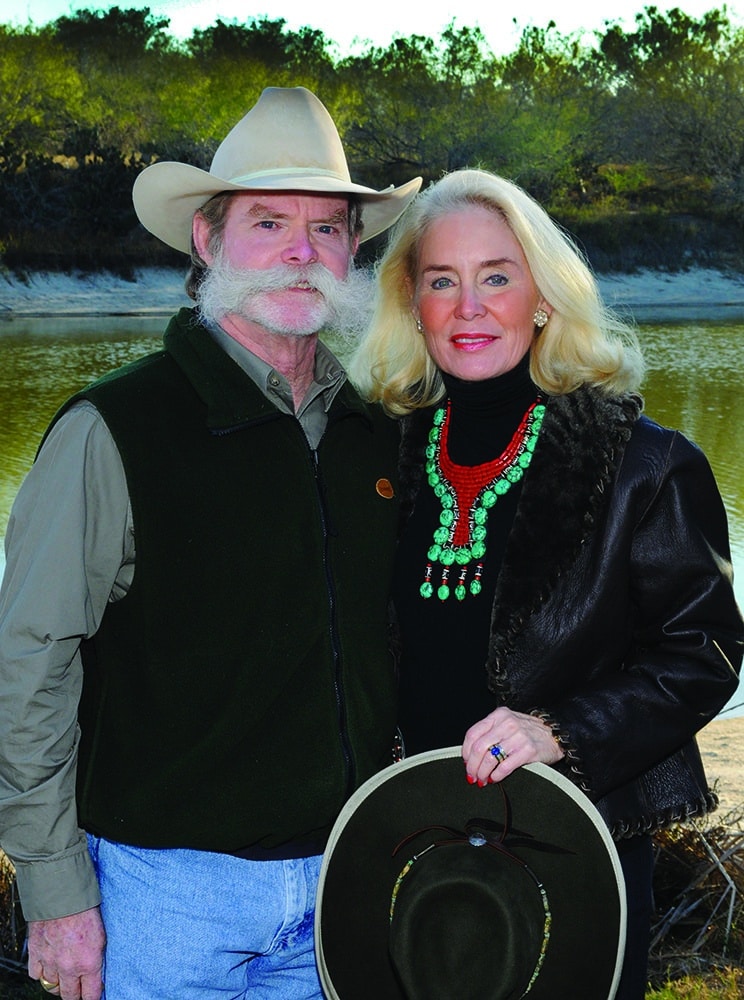

Those early days in the field left their mark. Today, as a 70-year-old man who has the world at his disposal, Kleberg counts hunting quail on King Ranch with his wife of 47 years, Janell, as his perfect day.

“Janell and I met as sophomores in college—and the rest, as they say, is history,” Kleberg said. “Whatever we’ve done, we’ve done it together.”

For the record, perfection includes being in the field by 8:00 a.m. with a hunting party of no more than four family members or friends, a Thermos of coffee and a picnic lunch so that the group and the English Pointers can make the most of the slightly damp 45° day ideal for scenting birds. The icing on the perfection cake is a post-picnic nap squeezed in between the morning and afternoon hunts that yield 20 flushed coveys.

“Then, we’d go home and pack the picnic for the next day,” Kleberg said.

Interest in quail prompted his grandfather, who served in Congress, and his great Uncle Bob, who operated the ranch, to hire Valgene “Val” Lehmann in 1945, earning King Ranch the distinction of being the first ranch in Texas to have a full-time private wildlife biologist. Lehmann completed groundbreaking work on quail, while originating concepts and tools including record keeping protocols that biologists and ranchers still use.

While hiring a private wildlife biologist in the mid-1940s was forward thinking, it was also a natural progression. Caesar Kleberg, a cousin, had embraced wildlife conservation as part of the ranch’s management ethos in the early 1900s. Caesar lived on King Ranch’s Norias Division near Raymondville. He noticed there weren’t many deer or quail on the ranch, so he implemented hunting rules almost a decade before the then-Texas Game & Fish Commission was created.

For instance, he forbade people to hunt deer during the rut to “allow them to procreate undisturbed.” He also required guests and family members to quit hunting quail around 4:30 p.m. so the birds’ roosting would not be disrupted. Hunting animals and birds as they traveled to and from water, a scarce resource in the Wild Horse Desert at that time, was also discouraged.

“Caesar Kleberg wanted to take care of white-tailed deer,” Kleberg said. “He figured out that we could improve the population by actively managing their habitat.”

Caesar, a contemporary of Richard and Bob, served as the “voice of wildlife” in that generation, imbuing the family with a commitment to conservation.

“My father learned from his and I learned from him,” Kleberg said. “Wildlife was ingrained since I was a small kid.”

This knowledge served him well. In the late 1970s, Kleberg, who was running the cattle, horse and farming divisions, had a conversation with King Ranch’s then-wildlife biologist Bill Kiel that fundamentally changed ranch operations. Hunting leases had just started taking hold in South Texas’ Golden Triangle counties, but hadn’t moved east.

“Bill said, ‘Tio, you know you’re leaving a lot of money on the table,’” Kleberg said. “I was incensed and asked, ‘What exactly do you mean, Bill?’”

Kiel shared some math. At the going rate of $6/acre on 800,000 acres, hunting leases could add $5 million to the ranch’s bottom line annually.

A two-hour conversation ensued and resulted with Kiel being charged with drawing up a lease contract and outlining potential leases that gave the family and the lessees privacy.

“The proposal was going to have a huge impact on the way my family viewed the land and how they thought about allowing people outside the family to come on the property,” Kleberg said. “I was faced with a hell of selling job.”

Eventually, the family was sold on the idea that required them to rethink many management practices including brush management. When livestock was the only income stream, brush was the enemy of productivity. For wildlife, brush was a necessary landscape component.

Kleberg and Kiel started with the Encino Division and laid out three leases in a manner that none of the headquarters are visible from any ranch road.

“Essentially, the written leases said, ‘We want to respect your privacy and we want you to respect our land,’” Kleberg said.

The initial lease was five years with an annual renewal beginning in the sixth year. King Ranch retained the right to immediately terminate a lease if there was any state game violation.

“We wanted the lease to be good for them, but it also had to be good for us,” Kleberg said.

It appears to have worked. Since the leases began in 1979, they have operated continuously, the game violation clause has never been invoked, and the lease manager that started it all is still running the hunts.

“We realized with optimization we could have both a profitable cattle and wildlife operation,” Kleberg said. “It’s possible to do both, but it forced us to look at the land differently.”

Community Service

Community Service

King Ranch’s legacy includes leadership and philanthropy as surely as land, livestock and wildlife.

“It’s part of our inheritance,” Kleberg said. “We just do it. If you don’t give back to the community, then you’re setting an example—and you can’t expect other people to give back either.”

The family’s commitment to community service can be traced back to Henrietta King. When the first families arrived to work on the ranch, she built a school for the children. Later when she donated the land where Kingsville was established, she also built schools and designated every fourth corner on the primary thoroughfares of King Street and Kleberg Avenue as sites for churches for the various denominations.

“As the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, she believed fervently in education and spiritual growth,” Kleberg said.

I’ve been involved since the very beginning when it was just a concept being discussed around a campfire. I joined the effort because I knew and respected many of the early principles including McLean Bowman and Steve Lewis. Even initially it spanned a large geographic distance and involved landowners from the Hill Country to South Texas. While I was already involved in wildlife management, I was attracted to their idea of aligning wildlife, which belonged to the states, with private property rights. If TWA didn’t speak on behalf of private landowners who managed wildlife, who would?

Her influence is still being felt. In 1912, she built a high school and deeded it to the city of Kingsville with the provision that it would remain in the city’s ownership as long as it was used to provide a free public education or other valuable public purpose. It was built in an era when public buildings were celebrations of architecture not soulless brick monoliths.

By the 1980s, the student population had outgrown the facility. It sat vacant until four years ago when Helen Groves, a member of King Ranch’s fourth generation, took it upon herself to revitalize the building. Providing funds from her foundation, she challenged the city to come up with a match and together they launched a public-private partnership to bring the building back to life as Kingsville’s new city hall.

Kleberg has dedicated his time and expertise primarily to agriculture and wildlife conservation-oriented organizations. Current affiliations include the American Quarter Horse Association and the board of directors for both the Caesar Kleberg Foundation for Wildlife Conservation and the East Foundation as well as the advisory board of the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University-Kingsville.

He is particularly excited about the potential impact of the East Foundation and its mission of supporting “wildlife conservation and other public benefits of ranching and private land stewardship.” The staff, working from a living laboratory of more than 215,000 acres of native South Texas left as a bequest of Kleberg’s cousin Robert East, achieves its mission through research, education and outreach.

The East Foundation is unique because it’s an operating foundation meaning it carries out its own research and education instead of providing grants to supports others’ activities. All of the East Foundation’s research, education and outreach take place in the context of a working ranch.

“In my opinion, there’s not another foundation that has the diversity of land and financial resources to conduct research that will have world-wide impact on ranching, wildlife and the general public’s understanding of the natural world,” Kleberg said.

As part of the outreach effort, the East Foundation works with local schools to introduce ranching, land stewardship and wildlife education into the curriculum and to host hands-on field days at the ranch.

“The biggest obstacle to helping people understand the intrinsic value of private stewardship on private lands is the people themselves,” Kleberg said. “Children and families generally don’t have outdoor experiences which lead to an outdoor connection. If we can introduce them to nature through curriculum and hands-on activities maybe they’ll be inspired to get outdoors. We have to help them draw the connection between their daily lives and the land.”

In his own family, he and Janell made a concerted effort to let their three children spend as much time as possible on the ranch during their formative years. Their daughter, Adrian, and sons, Chris and Jay, spent their summers working on the ranch. The experience created a bond that benefits the now-grown children and the land.

“As one of my friends once told me, ‘The best fertilizer a man can give his land is his shadow,’” Kleberg said. “Our kids’ connection to the ranch is much more than a name.”

The Future

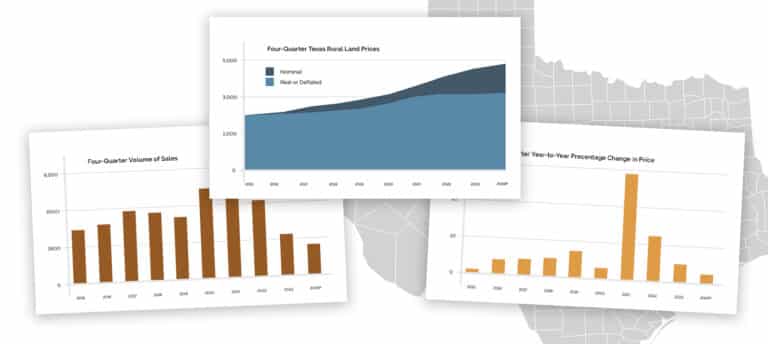

Keeping a ranch intact and in the family isn’t easy. Forces such as estate taxes, rising market values and decreasing production values buffet ranches, regardless of their size or storied history.

“The forces in play, particularly estate taxes, tend to drive the division and fragmentation of land,” Kleberg said.

When Henrietta King died in 1925, the estate tax bill was $3 million, which, in terms of current buying power, is the equivalent of $42 million. After dealing with the immediate crisis, family members determined it was critical to incorporate, which would spread ownership throughout numerous shareholders instead of concentrating it in the hands of few.

“Today, if we have a death in the family the impact from a financial standpoint is not nearly as dramatic as if the ranch were owned by three or four people,” Kleberg said.

In addition the family actively trains the next generation to take the reins. (The legacy now encompasses seven generations.) They have developed a leadership program where members of the sixth generation are invited by qualification and merit to sit on the board of directors.

“It gives them a chance to see what is going on and prevents them from just ‘being thrown on’ the board one day,” Kleberg said.

In addition, family members can apply for the summer internship program while they are in college, choosing to work in their field of interest whether it’s citrus, oil and gas, feed lots, wildlife or livestock. Immediately after college, the graduates can come to work for King Ranch in a structured one-year to two-year internship in a single area or many areas. The interns have an opportunity to learn how things are done in the various divisions and to make recommendations for improvements.

“They’ve gotten good educations, so they have new information and ideas that they bring to the business,” Kleberg said. “That’s how King Ranch will survive—every day we have to learn to do it better.”

This article appears in the fall 2016 issue of TEXAS LAND magazine. Visit www.landmagazines.com to read more and subscribe to future issues of both LAND magazine and TEXAS LAND magazine.

Community Service

Community Service