The late Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe once famously said that, “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” I suspect that Mr. Achebe made a reasonable point when he delivered that assessment, but I wonder if he anticipated that those “historians” would someday rise in the form of social media, fake news and a narrative that is now shaped by forces that defy the conventional wisdom of the past. Further, “the history of the hunt” no longer always glorifies the hunter! In fact, hunters rarely control the narrative that tends to define how our American society views hunters, hunting and the merits of the two.

The five-year study, National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, that has been conducted by the USFWS since 1955, revealed an alarming stat during the most recent cycle from the 2012–2016 period; that being an unprecedented drop in hunting license sales by almost 20 percent! This remarkable reduction in hunting license sales seems to paint an ominous picture for future of a “past-time” that has historically served as the chief funding mechanism for terrestrial wildlife conservation during the last 100+ years, not to mention the thought of losing an important part of our American cultural fabric. The percentage of our citizens that hunt is now less than five percent, which begs the question that relates to thresholds which render people and things as being irrelevant within the dynamic sideboards that shape societal acceptance; I suspect we are staring that threshold in the face, right now!

Now, our hunting community could simply fret over “better days gone by,” and we could, and certainly should, explore the reasons for diminution in hunting participation, but one thing that I would like to ponder is the absolute importance for our hunting community to do a better job of controlling the narrative on how we interact with society and how we project messages and images to those around us.

Social Media

Like it or not, social media has quickly emerged as the medium that people tend to glean their daily “news” and information from. This largely uncensored communication tool represents a vast sea of material that can create proverbial viral effects on how people view certain issues de jour. “Cecil The Lion” is a prime example of how social media can unjustly write its own history, as Mr. Achebe might have put it.

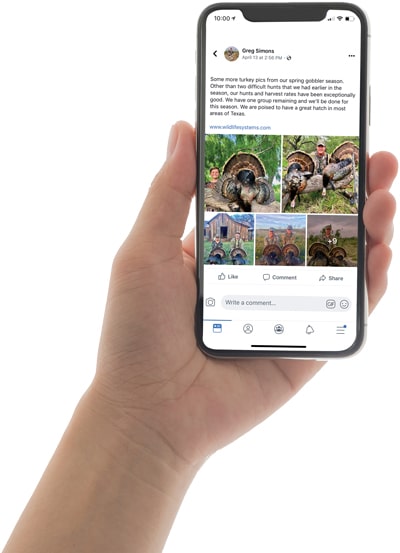

I’m not a social media expert, but I think that hunters, individually and collectively through NGOs, need to play the social media game smarter and harder. It fundamentally starts with being better stewards of what we post on social media, including hunting photos, as well as written material. I continue to see plenty of garbage that hunters post which can ultimately paint poor images of hunting, especially through distasteful photos that may evoke perceptions of hunters being low-grade people who are blood thirsty and of immoral character. Further, we fall short on sharing wholesome stories and messages that clearly articulate the beauty of the hunt and that reinforce messages that illustrate hunting as a conservation tool. From a narrative standpoint, we are often our worst enemy on this front.

Weaving of NGOs

Hunters have historically banded together through affiliation via various sportsmen’s groups. We can point to many different NGOs as shining examples of how hunters raise monies and channel sweat equity into causes that are good for hunting and good for our wildlife resources. However, where we seem to fall short with our hunting NGO efforts is through collectively working together to aggregate resources between these groups in a fashion that synergizes our broad efforts, while also creating efficiencies along the way. Some hunting NGOs have policies that preclude their option to financially support other similar groups; this seems a bit too self-focused to me.

Shaping Public Policy

For the sake of this article, the importance of controlling the narrative perhaps resonates no louder than that relating to laws that interact with hunting and wildlife. Fundamentally, with what is intended to be a democratic system where the will of the people is expressed through our elected officials and policy-makers, special interest groups who control the narrative through their strategic efforts are generally well-positioned to advance their agendas. However, once again, our hunting community tends to not be collectively well-organized when it comes to media outreach, public testimony, legislative relationship building and general educational outreach. Pressures of society tend to shape public policy; these days, those pressures are generally greater from the non-hunting community than from hunters. Hunters need to learn to play that game harder and smarter.

Addressing the Slippery Slopes

The American ideal of hunter-conservationists emerged out of necessity during the late 1800s, when much of our country’s wildlife were on the throes of a colossal collapse, and then evolved over time to be reflective of the times. And as “times changed,” so did certain laws and practices that were deemed as protectionary of the whole, with some of those intra-community debates leading to a bloody process in the name of doing what was right for the resource and for the long-term health of our hunting heritage. When such policy discussions are initiated by concerned hunters and wildlife professionals, these discussions tend to create chaos within our own ranks, causing turmoil and infighting that can be self-damaging, and thus presenting paradoxical conundrums. But when you distill it down to its rudiment, the fact remains that our hunting and game management practices must be reasonably defensible in the eyes of our societal majority, or we will otherwise be squeezed out. . . . That may not be your rule, nor mine, but that’s simply the way it works these days. The barriers of these slippery slopes must be more honestly and actively addressed, otherwise our advocacy efforts and our messages will largely fall on the deaf ears of a discerning public that is increasingly intolerant of practices that are deemed as indefensible.

Controlling the narrative, regardless of the task at hand, can certainly be over-simplified, and I recognize that there are many other pressures facing the future of hunting than those that I’ve pointed out in this article. Bottom line, however, is that our hunting community must do a better job of stepping up to the plate and striving for excellence in our ability to control the narrative. We must do a better job with public relations, we must generate stronger messaging strategies that incorporate better repetition structure on more fronts and we must do a better job of managing our own house. Otherwise, we will lose the battle. . . . We are losing the battle right now, which is partially evidenced through an almost 20 percent reduction in hunting license sales from 2012 to 2016!