“I was five years old and sitting on my uncle’s shoulders, when I fell in love with the land,” said Jarvis, who now lives in Crested Butte, Colorado. “Every afternoon of every summer, he and I explored the hardwood timber of the Mississippi Delta around Vicksburg. When I got too big to carry, I walked fast to keep up.”

Jarvis, who was reared in Houston, made his multi-faceted career as a farmer, custom harvester, land broker and land developer, at their confluence in Mississippi. The Magnolia State is home to the family’s legacy that began in the 1880s when George T. Houston (pronounced How-stun), a Chicago sawmill owner, ventured south and saw the untapped potential of Mississippi’s virgin hardwood forests. Houston purchased 200,000 acres of land and established sawmills in Amory, Spanish Fort and Vicksburg. Using a novel approach, Houston sold land for no money down in exchange for the opportunity to cut a set percentage of the hardwood.

Jarvis, who was reared in Houston, made his multi-faceted career as a farmer, custom harvester, land broker and land developer, at their confluence in Mississippi. The Magnolia State is home to the family’s legacy that began in the 1880s when George T. Houston (pronounced How-stun), a Chicago sawmill owner, ventured south and saw the untapped potential of Mississippi’s virgin hardwood forests. Houston purchased 200,000 acres of land and established sawmills in Amory, Spanish Fort and Vicksburg. Using a novel approach, Houston sold land for no money down in exchange for the opportunity to cut a set percentage of the hardwood.

The business passed from Houston to his three sons, George Jr., Philip and Horace. The Cornell graduates, who all served in WWI, operated the family business as Houston Brothers, until they divided their interests in the 1930s. Jarvis’ maternal grandfather Philip bequeathed his portion, based in Vicksburg, to his children: George III known as Ted and his daughter Ruth.

“My land management philosophy was born in the Mississippi Delta,” Jarvis said. “As stewards, we have a duty to use the land with respect and leave it better than we found it, but we need to enjoy it, too.”

He continued, “No one who talks about me ever will say, ‘He spent too much time at his computer.'”

The passion

The relationship between Ted Houston and Jarvis transcended that of many uncles and nephews.

“He was a father figure, a role model and a mentor—all rolled into one,” Jarvis said.

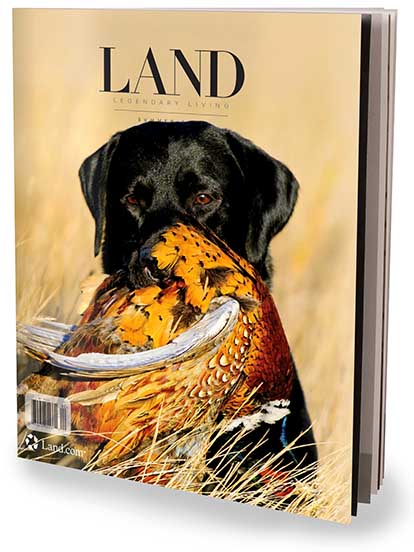

When Jarvis came to spend the summer with his bachelor uncle, the duo would rise early and go to the office where Houston would work and Jarvis would “play” with the secretaries until lunch. Then they’d head to the woods to walk, talk, fish, throw rocks, look at critters and, on some properties, watch the Mississippi River roll by. Houston took Jarvis on his first hunt, “a memorable duck hunt.” Over his lifetime, Jarvis grew to be an avid wingshooter and whitetail deer hunter.

“I didn’t realize there was any other alternative than to be outside,” said Jarvis, who spent a recent day riding his motorcycle over more than 100 miles of mountain trails near his home with a friend and a chainsaw, so he could clear low-hanging branches and fallen trees blocking the trail for other biking enthusiasts. “I love waking up early each day to see what beauty God has in store.”

“I didn’t realize there was any other alternative than to be outside,” said Jarvis, who spent a recent day riding his motorcycle over more than 100 miles of mountain trails near his home with a friend and a chainsaw, so he could clear low-hanging branches and fallen trees blocking the trail for other biking enthusiasts. “I love waking up early each day to see what beauty God has in store.”

According to Jarvis, his mother described him as “very spirited” when he was a child and she was talking with company; he declined to say what she called him in private.

“I was that kid who thought surfing was much more important than spelling,” said Jarvis laughing. “Actually, though, I was a bit psychic and foresaw the invention of ‘spell check,’ so I knew spelling class was just a waste of time.”

Jarvis began skiing in the Rockies when he was 12, further expanding his set of outdoor interests that now also include mountain biking and dirt biking, and creating another home away from home for him. Years later, he introduced his wife, Lauret, to the mountains. She was immediately smitten by the landscape and the lifestyle. The couple, who lived in Vicksburg, acquired a second home in Crested Butte in 2005. It became their primary residence in 2014.

“We’re outdoors people and Colorado is an outdoors place,” Jarvis said. “It’s a perfect fit for our personalities—and for our shared passions.”

The confluence

In 1985 just weeks shy of his graduation from Texas A&M University, Jarvis went to visit his beloved uncle who was undergoing cancer treatment at M.D. Anderson. The 25-year-old went prepared to learn the secret of life. When asked, the older man laid out his simple philosophy of life.

Have integrity. Be an honest man of your word—and don’t trust anybody,” Jarvis recalled.

“Have integrity. Be an honest man of your word—and don’t trust anybody,” Jarvis recalled.

Then the older man forever altered the course of Jarvis’ life by saying, “I’m going to be calling you soon and when I do you pack your stuff and go to Vicksburg.”

When Jarvis objected, using his impending graduation as the rationale, his uncle replied, “Son, you graduated today.”

When Jarvis objected, using his impending graduation as the rationale, his uncle replied, “Son, you graduated today.”

The call came when Jarvis had five weeks left in his college career. With his best friend’s help, Jarvis packed his belongings in College Station and trekked to Vicksburg, arriving in a matter of days. He rented the first apartment he found and immediately plunged into a fiery baptism.

“I’d never looked at my uncle’s business with anything but a kid’s rose-colored glasses,” Jarvis said.

A careful examination revealed the business was carrying land debt without the protection of life insurance and was subject to a large estate tax bill.

The most pressing task was establishing the value of the business, which consisted of 22,000 acres of land that was 50 percent timber and 50 percent farmland. There were 24 separate farms and 18 timbered tracts.

For about two years, Jarvis and his appraiser wrangled with the IRS and its appraiser, eventually settling on a value and finalizing the estate. In the process he got to know each parcel intimately. He also got to know the farm operators and determined he should farm some of the land himself instead of leasing it out.

“I charged myself rent and paid it directly to the estate,” he said.

To save money on his own farms and generate additional revenue by contracting for other farmers, Jarvis and his long-time friend Benny Street formed a custom harvesting business. The business partners needed start-up capital.

Ted had served on a local bank board. Jarvis introduced himself at the bank by announcing he was Ted’s nephew. The banker responded, “If you’re Ted’s boy, you’re our boy.”

“My uncle left me the legacy of his good name,” Jarvis said, noting he and this bank, which he still uses today, went on to do millions of dollars in business over the course of his career. “I still believe in the power and commitment of a handshake.”

During this same period, Jarvis earned his land broker’s license because the entrepreneur realized he “would likely be buying and selling a lot of land.” He did.

To further complicate the situation, the ’80s happened. The bottom fell out of the oil, land and commodity markets including soy beans which were the preferred cash crop in the Delta. Jarvis, like many farmers, found himself in negotiations with the federal land bank and looking for new revenue streams. He found his afield.

To escape the pressure cooker of business, Jarvis would get up and hunt dove, duck or whitetail deer from daybreak to about 8 a.m. almost every day during their respective seasons before tackling the day’s work. Coming from Texas, where the practice of leasing hunting rights was widespread, he saw potential. His portfolio of properties he was managing for the estate included three of arguably the best duck properties in Mississippi.

“The highest and best use of a farm’s marginally productive land wasn’t producing soybeans, it was supporting wildlife habitat and providing recreational opportunities,” Jarvis said.

In Mississippi, he was one of the early pioneers of using federal cost-share conservation programs including the Conservation Reserve Program and the Wetlands Reserve Program to move marginal cropland out of production and re-establish natural habitat. He applied this on land he purchased from the estate to develop himself as well as on land he kept as part of the business. He also shared what he was learning with his fellow landowners.

“By my rough count, I was responsible for planting more than 925,000 hardwood trees in four counties in the Delta,” he said.

In addition to rehabbing the habitat, Jarvis developed the necessary infrastructure such as levees, wells, roads, food plots and even lodges to take his properties to the next level. Then, he found buyers who appreciated what the land had become and what it could continue to be. Next, Jarvis, once again partnering with Street in a consulting business, began offering wildlife and land development services to other Mississippi landowners.

“There is something about land that speaks to me,” Jarvis said. “I could go on a piece of property, even one that was rough as hell, close my eyes and envision exactly what needed to be done so it could express its potential.”

“There is something about land that speaks to me,” Jarvis said. “I could go on a piece of property, even one that was rough as hell, close my eyes and envision exactly what needed to be done so it could express its potential.”

Their clients included the who’s who of Mississippi such as Jim Kennedy, founder of Cox Communications, Richard McRae, founder of McRae’s department stores, and Howard Brent, a Mississippi River tugboat magnate. In the case of the consulting business, many times the job was “taking a four and transforming it to a 10.”

From 1989 until 2006 when Jarvis sold his last big project, Jarvis improved 13 different properties ranging in size from 500 acres to 3,500 acres.

From 1989 until 2006 when Jarvis sold his last big project, Jarvis improved 13 different properties ranging in size from 500 acres to 3,500 acres.

“I managed 22,000 acres and touched an additional 25,000 acres,” Jarvis said. “Six of these projects are considered to be among the finest hunting properties in Mississippi—and arguably in the nation. All are family owned and operated for family and invited guests. Most could not be purchased, only inherited or married into.”

With that said, a very rare opportunity to own a property that Jarvis originally developed for himself, is now for sale by its current owner. It still bears the name of the Houston family estate, Forestaire, of which it was part.

View the Forestaire Plantation on Lands of America

“This property is nothing short of magnificent—and it is capable of putting on one of the best duck shows at dusk that any duck hunter could possibly ask for,” Jarvis said.

The satisfaction

Although Jarvis is pursuing different business interests now, he still returns to Mississippi to hunt ducks, visit friends and reap the satisfying reward of watching the landscape mature, improve and change. Hardwood saplings that were once the diameters of pencils can now support a large lock-on tree stand and a hunter’s weight. Ducks following the genetic flyway map of their ancestors now bob in ponds and restored wetlands that were once soybean fields. Whitetail deer abound in the timber. Next generations of multiple families are being raised to enjoy and appreciate the outdoors.

The vision is particularly sweet these days because now Jarvis takes nothing for granted. In 2012, his intestine ruptured while he was hunting elk in the remote mountain backcountry of Colorado. Several times doctors measured his survival chances in small percentages. He defied their odds.

The vision is particularly sweet these days because now Jarvis takes nothing for granted. In 2012, his intestine ruptured while he was hunting elk in the remote mountain backcountry of Colorado. Several times doctors measured his survival chances in small percentages. He defied their odds.

“None of us are guaranteed a tomorrow, so what I do today is important because I am exchanging a day of my life for it,” Jarvis said. “I exchanged a lot of days of my life for those projects—and they still matter to me, to their owners and to the natural world.”

A story worth telling

The One About Theodore Roosevelt’s Nickname and His Rifle

“In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt, who was a hunting conservationist, was invited to the Mississippi Delta for a black bear hunt. At the time, there were a lot of black bears in the timber, and the local tradition was to hunt them on horseback with hounds. The hounds would bay the bears, allowing a hunter to get a shot.

After several days of hunting, the locals hadn’t been able to find a bear for the president. At some point he left the hunting party, but Holt Collier, the group’s leader, continued to look for a bear. He found one.

As the story goes, Holt rode his horse up to the bear and hit it in the head with his rifle’s butt. It knocked the bear silly, so they roped him, tied him to a tree, and sent someone to get the president with the message: ‘We found a bear for you.’

When the president arrived, he could tell the bear wasn’t quite right. Then, he spotted the rope and flat out refused to kill a captive bear. It was this act of mercy that earned him the nickname ‘Teddy.’

All of the area’s prominent citizens, of which my great-grandfather was one, were included in the hunt and associated festivities. My great-uncle, who was a boy at the time, acted as Teddy Roosevelt’s gopher doing things like saddling his horse and cleaning his gun.

At the closing rally, the president called my great-uncle over and said, ‘Thank you for taking such good care of me, while I was here. I want you to have my rifle.’

My great-uncle used the rifle and then passed it on to my uncle Ted Houston. It is on display at the Old Courthouse Museum in Vicksburg. Before Uncle Ted passed it to me, he took it out of the museum and invited me to go shoot it with him. We knocked an oil can out of tree three times out of three shots.

My great-uncle used the rifle and then passed it on to my uncle Ted Houston. It is on display at the Old Courthouse Museum in Vicksburg. Before Uncle Ted passed it to me, he took it out of the museum and invited me to go shoot it with him. We knocked an oil can out of tree three times out of three shots.

On Christmas a few years ago, I gave the gun to my son. Before I did though we showed up at the museum, much to their surprise and worry, and took the gun from the display case to Valley Park Plantation. It is one of my early projects that I sold to a good friend Hunter Fordice whose Mississippi roots go back as far as mine. I killed a deer with the rifle, my son killed a deer with the rifle, and my godson killed a deer with the rifle.

When we were done, we cleaned and oiled the gun and took it back to the museum. It was a great full circle experience. I like to think all my ancestors—and Teddy Roosevelt—smiled.”

Another story worth telling

The One About Winning at the U.S. Supreme Court

“Stack Island, which is about 2,000 acres of land located in Issaquena County, Mississippi, came into our family’s ownership in 1888. At that time, the navigation channel was on the Louisiana side. The river was non-navigable on the Mississippi side. In fact, when the water got low there was a sandbar that attached the island to the Mississippi side.

Over time, especially before there were levees managing the flow of the river, floods and the current eroded the sand on the Mississippi side of the island and deposited it on the Louisiana side. By 1954, the channel on the Louisiana side became non-navigable and the channel on the Mississippi side became deep and wide enough to become the primary navigable channel.

In the 1980s, Louisiana, noting the change, claimed that Stack Island was now its property. I said, ‘Oh hell no.’ Stack Island was one of the places that I’d come to know and love from atop my uncle’s shoulders.

And the facts backed my family’s position. In an ordinary river boundary dispute, the main channel of navigation defines the boundary, which moves as the channel shifts through erosion and redistribution. But if the river flows around an island, there is an exception to this rule. Once a boundary is determined on one side of an island it remains, even if the main channel shifts from one side to the other.

It was a profound period in my life. The case entered federal court on July 29, 1986, and was finally ruled on by the U.S. Supreme Court on October 31, 1995. At one point my mother, who was a 25 percent owner in the island, wanted to withdraw from the lawsuit because of the cost, the time and the emotional toll. I told her, ‘Mom, trust me on this. The facts say we’re right.’

It was a roller coaster. We made it to the U.S. Supreme Court only to have them appoint a special magistrate to gather additional facts during a trial in Vicksburg. The opposing counsel tried every trick in the book including planting a story in the local paper that “Stack Island was a no man’s land,” so that on opening morning of deer season one year, I arrived to find 15 tents worth of gun-toting people set up on the island preparing to hunt.

The special magistrate found in our favor, but Louisiana appealed so we ended up back at the U.S. Supreme Court with more than 400 pieces of evidence in our possession.

The special magistrate found in our favor, but Louisiana appealed so we ended up back at the U.S. Supreme Court with more than 400 pieces of evidence in our possession. If you’ve never been there, it is an awe-inspiring place. There are a lot of rules for decorum of the presenting attorneys and the spectators but none for the judges. They talk over one another, ask questions before an attorney is done answering a colleague’s question—it is high-level legal professional wrestling.

Our attorney, Bobby Bailess of Vicksburg, Mississippi, gives credit to an 1881 shoreline survey as being the crucial piece of evidence that turned the tide in our favor. I give credit to him. He has the most incredible ability to grasp facts and details of anyone I’ve ever seen. Attorneys presenting in front of the Supreme Court aren’t allowed to use notes.

When the opposing counsel was in the center ring and the justices were pummeling him with questions, he’d go red and say, ‘I don’t recall exactly.’ It happened so often that my mother whispered under her breath, ‘The dog ate his homework—again.’ I laughed so loudly that the court police came over and offered to escort me out if I didn’t control myself.

Bobby, on the other hand, could point the justices to the exact page and paragraph every time. He was nothing short of amazing.

The only thing more amazing was the feeling that came from winning—and keeping a piece of the family’s legacy in the family where it rightfully belonged.”