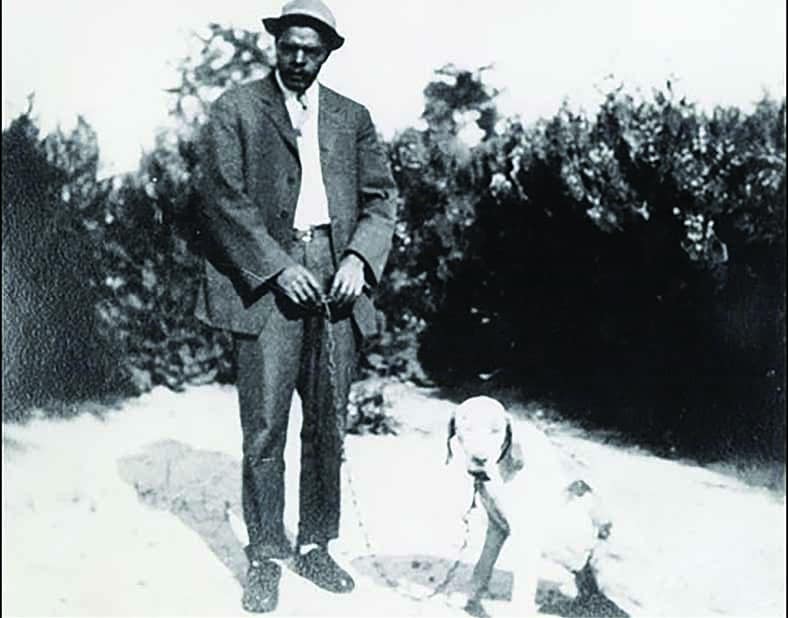

Main image caption: From left: Clinton Hutto, Willie Battles, Jr. and Harry Cromartie

Every March in the Red Hills Region around the bobwhite quail hunting capital of Thomasville, Georgia, an invitation-only field trial has taken place for the past 36 years that celebrates the rich tradition of African-American bird dog trainers who have been thriving on the local plantations for generations.

Officially the group is named the Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club, although it’s commonly called the “Black Dog Handlers Association.” It was started in 1981 by a handful of prominent African-American dog trainers who wanted to cut loose with their own raucous family atmosphere, while at the same time exhibit their skills to the next generation of dog-trainer hopefuls amid the fierce competition of the plantations they represented.

I’ve hunted local quail with Monty Lewis, a lifelong resident of the Red Hills Region, owner of Plantation Propane & Petroleum in Thomasville and avid quail hunter. A gallery observer of the field trials, he portrayed the occasion as a “celebration of life in terms of dog training passed down through multiple generations and a love for the woods, the dogs, the horses and the outdoor men that made a living from the sport of bobwhite quail hunting.”

Having moved to Thomasville in December 2015, I missed this year’s Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club trials by three months. It’s always held the first of week of March, immediately following close of quail season in Georgia and Florida.

I had originally heard about the Club from auto mechanic Edwin Doolittle, who works at German Import Service in Thomasville – the garage that services vehicles for several of the plantations and their owners.

What I would discover is a group of extraordinary bird-dog handlers quite modest about self-promotion, yet willing to respectfully share their world under circumstances that protected all-concerned. I’d find out that gaining their confidence was a gradual process where some key individuals vouched for me along the way until word spread that I could be entrusted with their history and calling.

My journey started with Mr. Doolittle, who with his wife Hope, also raise the Tennessee Walking Horses favored for their gentle gait on the plantations’ wild quail hunts. Over the past six years Ms. Doolittle has become official photographer of the Club’s field trials. The Doolittles of course were regulars at the event, so with their assistance and other insiders eager to finally bring the story to light, I gradually peeled back the remarkable account of the “Black Dog Handlers Association.”

The Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club spun off from the Georgia-Florida Field Trial Club of the Red Hills Region, which for the past 100 years has conducted field trials geared toward the society of plantation owners. At the owners’ annual events, which rotate between plantations, the African-American dog trainers worked in support positions to help ensure smooth operations. Over the years, people involved grew to realize that these men deserved higher visibility through a competition devoted entirely to their own culture and talents.

In conversations with 15 African-American trainers in the Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club, a consensus emerged that the purpose for its formation was to showcase their skills once passed along from their grandfathers, fathers and uncles who lived and worked on neighboring quail plantations.

Dog handler Willie Sims of Kelly Pond Plantation has competed in the Club’s field trials for about 20 years. “My grandfathers on both sides of the family did it,” he said. “They worked on plantations too. I saw the older trainers doing it and thought that was the neatest thing in the world. I started training dogs after graduating from high school in Atlanta. I think it’s just a great bunch of men, you know.” He placed second in the 2015 field trials.

Following my trail of contacts, one bright autumn morning led me down a sandy track on Elsoma Plantation to meet dog handlers and Club members Harry Cromartie, Clinton Hutto and Willie Battles, Jr. Impending quail season charged the atmosphere as dappled sunlight angled through the longleaf pine forest, with dogs barking from the nearby kennels breaking the glorious silence. I parked at a cluster of wood outbuildings where we soon stood beneath the pine canopy, talking about the men’s heritage in the Red Hills Region bird-dog culture.

Mr. Hutto recounted that he had grown up on Sunny Hill Plantation in Tallahassee, Florida. Of the Red Hills bird-dog culture he said “I was raised around it.”

For Mr. Cromartie, his career began at nearby Longpine Plantation “when I first graduated high school.” Over the decades he worked long stints at private plantations in the area training dogs and driving mule-drawn wagons.

And Mr. Battles was initiated into the bird-dog world at age 16 by his godfather who worked on a plantation.

During our conversation I learned that many of them were introduced to the profession through their families, although actually committed to it starting with after-school, summer or weekend plantation jobs. Working closely with their mentors, they benefited from the generations of oral know-how disseminated throughout the plantations. For them, the Club’s field trials opened the door of the African-American, dog-training traditions to friends, family and aspiring members.

We want to keep the legacy going, of what our ancestors did to run the dogs.

— Willie Battles, Jr.

“We want to keep the legacy going, of what our ancestors did to run the dogs,” Mr. Battles said of the field trials. “It’s a good learning experience for the young guys for what they need to know.”

The three men laughed that the 44-year-old Mr. Battles is considered one of the young members in the Club, and appreciated that even contenders in their twenties are eager to participate.

For those newcomers, entering the Club immerses them into an “extended family,” as Mr. Clinton described it, which reaches beyond long-cherished tips for flushing, retrieving and holding steady.

Over and above a personal support network, the Club is a prized ticket to become a field trial challenger, where the men “have fun after a hard season of hunting,” acknowledged Mr. Battles.

Dog-training skills are certainly essential, yet nearly everyone warned that the occasion isn’t for the thin-skinned.

“There’s a lot of trash talking,” Mr. Battles cautioned, tongue in cheek.

“Our field trials are a little different than most, more fun and more razzing each other,” said one African-American trainer who’s been a Club member for about 10 years. “I just enjoy having a great day and may the best man win.”

It’s a bragging rights club to see who has the best dogs.

— Bernard Parker

“It’s a bragging rights club to see who has the best dogs,” said Bernard Parker of Four Oaks Plantation. He won the first-place Governor’s Cup trophy in 2011.

I spent one morning at Four Oaks Plantation speaking with Mr. Parker and fellow dog handler Curtis Brooks. Quail season was only weeks away and I marveled at the choreography of the Four Oaks crew harnessing the mules to bird wagons, saddling horses for the scouts and running dogs in preparation for the hunting season.

Once ready, six of us headed into the fields, exercising the animals, checking equipment and flushing about 10 coveys of wild quail in an amazing, timeless spectacle across the sumptuous landscape.

A 27-year veteran of the Club, Mr. Brooks agreed that the field trials were “honorable and fun and we like to talk trash to one another.”

Joe Fryson is a Club member who is now retired. We visited at his house, where he kept two horses, on a pastoral side road off Route 319, also designated “Plantation Highway” where it connects Florida and Georgia through the Red Hills Region. “We have our kids involved so they can see what we’re doing, it’s just a big family day,” he said. He discussed how the Club’s field trials encourage the members’ families “to watch and visit us.” A three-time winner, he took top spot in 1997, 1999 and 2002.

As veteran Club members like Mr. Fryson approach retirement age, the field trials have come to play a pivotal role in attracting younger local African-Americans interested in training bird dogs.

One Club member said of the field trials, “I just love it. I love to watch the great dog work. But I’m the last one in my family who’s training dogs. None of my boys want to do it, because there’s long hours involved.”

While I sat with Mr. Brooks at a picnic table under a majestic oak tree near a barn, he told me that “the Club helps us bring in younger trainers.” He was delighted that during the 2016 field trials “three of the younger guys beat out us old fellas. We were very excited about it. Now us older guys need to work harder.”

In fact, one of the younger trainers who did extremely well in those field trails was his son, Curtis Brooks, Jr.—a Club member for the past six years. Known as “Junior,” he started working with Mr. Brooks on the plantations at age 16 by riding horses and scouting for wild quail. “I used to take my son on the Black field trials, and we’d ride the same horse and he fell in love with it.”

We’re trying to bring younger people into the club who want to be dog trainers so they could carry it on.

— Neal Carter, Jr.

“We’re trying to bring younger people into the club who want to be dog trainers so they could carry it on,” said Neal Carter, Jr., who was involved in organizing the “Black Dog Handlers Association” and currently serves as its president. At 64, he garnered the Governor’s Cup four times so far and is looking toward retirement.

Mr. Carter comes from a long line of Red Hills dog handlers including his grandfather and several uncles. Having grown up on Sinkola, he started formal bird-dog training on the plantation at 18 years old under Wallace Stephens. Mr. Carter was appointed Sinkola’s lead trainer in 1992 after Mr. Stephens retired. Talking in the rustic cabin that served as Sinkola’s office, he reflected “my son moved to Atlanta and my two daughters aren’t interested in training dogs either.”

He traced the Club’s origins to 1979, when several African-American bird-dog trainers, including himself, started the conversations with quail plantation owners about forming their group.

“We went to all the plantations where the guys worked to find out where we could hold it, and got permission from the owners to take the dogs and horses off their property for our first field trial at Kelly Pond Plantation,” Mr. Carter recounted.

The barn at Kelly Pond Plantation where the first field trial took place for the Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club.

Those trainers received enthusiastic sponsorship and support from the owners, which continues today as membership has languidly risen from the original 24 to 36. Ag-Pro, a regional farm equipment company, has sponsored the field trial’s soul-food lunch. Lawson Mack, a chef in Thomasville, dishes up collard greens, smoked chicken, ribs, black-eyed peas, corn bread and pigs feet.

Mr. Carter’s home base of Sinkola is managed by Gates Kirkham, fifth generation of the Hanna family that has pioneered quail plantations in the Red Hills Region since the late 1890s. Mr. Kirkham came of age on Sinkola, essentially growing up with Mr. Carter.

“We’ve been totally supportive of their group,” he said.

Mr. Kirkham’s relative, Charles Chapin III, explained “when they got started the first president of the organization was LeRoy Bull Clayton. We always called him Bull. I was involved with him in starting the group and happy to do whatever we could to support it.”

Warren Bicknell, who is related to Mr. Kirkham and Mr. Chapin, has been participating in the Club’s field trials since their start. “Neal Carter is like a brother to me. It’s just the way things were. I think it was an automatic to support them. They deserved to be supported and we care about them very much.”

Like other plantation owners and their relatives, Mr. Bicknell, Mr. Kirkham and Mr. Chapin supplied the dogs, horses, wagons, money, land, served as timekeepers and judges and generally provided whatever was necessary for the field trials to succeed.

“They thought it would be fun to have a field trial of their own,” Mr. Chapin recollected “and a lot of the owners thought it was a great idea. Some owners made substantial contributions. Every year someone offers to let them run the trial on their place. I’ve judged it once and my wife has judged it once. We all have a hell of a good time.”

Although a few of the Club’s African-American trainers run their own dogs, they prefer the plantations’ dogs that they worked with daily. The upshot is that the field trials developed into an inter-plantation rivalry that cranked up the competitive heat.

“We get to take the number-one dog from the plantation kennel and compete against our buddies with it,” said a Club member.

“Over the years, they’ve become more competitive and that’s always more fun,” said Mr. Bicknell. “Everybody loves their dogs. It’s really a joy to see them work. It’s a great tradition that hopefully it will carry on. I’ve always tried to participate as a timekeeper and I always look forward to it.”

The earliest field trials became instant hits, to the extent that Florida Governor Lawton Chiles would attend whenever possible to award the first-prize Governor’s Cup trophy.

Mr. Bicknell mentioned that “Lawton Chiles gave out the trophies for it for years. Those field trials are steeped in tradition.”

As with Mr. Kirkham, Mr. Bicknell and Mr. Chapin, quail plantations in the Red Hills Region have been passed down through families for generations, although more recently properties are being bought by high net-worth individuals in Wall Street, energy and media who can afford the $10-to-$30 million purchase price plus ongoing expenses of maintaining large staffs year-round.

Approximately 150 private quail plantations are spread across the Red Hills Region’s 300,000-acres. The land is home to a considerable portion of surviving native longleaf pine forests remaining in the United States, which as it turns out, is quite hospitable to bobwhite quail. The plantation owners can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars annually on land management to ensure the propagation of wild quail for the enjoyment of their families, friends and business associates, while at the same time preserving vast swaths of indigenous ecosystems against the northward urban development from Florida’s capital of Tallahassee.

The private plantation owners often benefit from their neighbor, the Tall Timbers Research Station in Tallahassee. Tall Timbers is a pioneer in conservation, fire ecology and game bird management. The non-profit organization provides invaluable data and education to the plantations owners in their quest to create and maintain pristine bobwhite quail habitats. Along with the owners’ desire to realize the Red Hills Region’s natural beauty comes their approach to maintaining wild quail hunts as experienced in the late 1800s by the influx of industrialists and investors from the North and Midwest.

So with the unique mix of land conservation, traditional mule-drawn bird buggies, walking horses and double guns the African-American dog trainers prosper in a historic milieu with a progressive sensibility.

To many outsiders, the word “plantation” still resonates of Southern slavery and segregation. Dr. Becky Malphus moved to Thomasville in 1994 as a veterinarian at the Clanton-Malphus-Hodges Veterinary Hospital—one of the top dog-care resources for the quail plantations. When she visited her first Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club field trials and saw only African-American trainers competing her impression was “why is it that way?” she told me, until she understood shortly afterwards “that it’s a real tradition where the guys showcase how they handle and communicate with their dogs. It’s a much more traditional trial, a big, good family environment.” She’s been involved with the group for 22 years.

Dr. Malphus’ preliminary reaction should come as no surprise to anyone except those people intimately involved with the Club.

In the book “African-American Life on the Southern Hunting Plantation” written by Titus Brown and James “Jack” Hadley, who owns the Jack Hadley Black History Museum in Thomasville, the authors wrote “African Americans who worked on the hunting plantations in the first half of the 20th century is a neglected topic by historians.”

African-Americans certainly endured plantation hardships up through the civil war. Finally in 1865 the agrarian economy proved unsustainable without slave labor. The gentry of the Gilded Age swooped in on their former enemies to purchase the defunct plantations at distressed prices.

Their motivation was actually to escape the freezing winters. These freshly minted owners converted the plantations into private seasonal resorts and took up the newly fashionable pursuit of hunting bobwhite quail. The plantations around Thomasville in particular proved especially popular since the town survived the Civil War untouched while it also became a southernmost terminus for railroads – attracting the original snowbirds who contributed to the booming economy. Meanwhile, the surviving slaves and their families were offered jobs on the plantations, in turn engendering generations of dog handlers, scouts and horsemen whose descendants continue the practices.

Lucille Glenn Morris recounted her life in “African-American Life on the Southern Hunting Plantation” during the early 1900s on Susina Plantation in the Red Hills town of Beachton, Georgia by starting: “The name plantation symbolizes, for some people, a system of servitude in which workers were subjugated and exploited by this system for economic gain. Susina Plantation, where I grew up defied that image. My early life experiences at Susina Plantation can best be described as enriching, nurturing, and enjoyable. Love, brotherhood, industry, responsibility, and goal setting were some of the values instilled in a loveable, family-like setting.”

For Jay Kimbrel, manager of the Four Oaks Plantation, these early generations of African-Americans involved in bobwhite quail hunting constructively influenced his life and career.

Mr. Kimbrel grew up on his grandparents’ farm next to Ichauway—one of the region’s most prominent plantations created by Coca Cola President Robert Woodruff in 1929 on about 36,000 acres of prime bobwhite quail hunting land.

Although Mr. Kimbrel spends most of his waking hours in the Four Oaks Plantation office, he fondly recalled those halcyon days when the African-American dog trainers and wagon drivers of Ichauway instructed him on the basics of guiding, courtesy and hospitality.

“They taught me the traditions,” he said. “They were all very good to me in helping understand how to host people and manage the lifestyle that gradually got me out of accounting and into the hospitality business of quail hunting.”

Perhaps Mr. Hutto of Elsoma Plantation characterized the Club and field trials best when he said of the experience “it’s really joyful.”

Irwin Greenstein is the publisher of Shotgun Life. You can reach him at contact@shotgunlife.com.

This article appears in the winter 2017 issue of LAND magazine. Visit www.landmagazines.com to read more and subscribe to future issues of both LAND magazine and TEXAS LAND magazine.